This week I have a special treat for you pulp fans! I’m pleased to feature a guest-blogger G.W. Thomas here on That’s Pulp! That’s right, instead of my usual drivel, you get to read something from someone who actually knows what he is talking about.

G.W. Thomas’ writing has appeared in Writer’s Digest, The Armchair Detective, Black October Magazine and over 400 other publications. He is currently writing for Michael May’s Adventureblog. He is the author of the horror-noir series, The Book Collector. His website is gwthomas.org.

Below, he takes time out of his busy schedule to fascinate you with the matter of the science-fiction pulp covers that featured….

How bug-eyed was my monster?

(with apologies To Robert Bloch)

How fair is the label of the BEM (or bug-eyed monster) in 1930s science fiction? If you believe the detractors, every cover had such a beast slavering out its lust for some buxom, space-faring woman. And just what does “bug-eyed” mean anyway? Wikipedia defines it as “huge, oversized or compound eyes.” Let’s put this to the test.

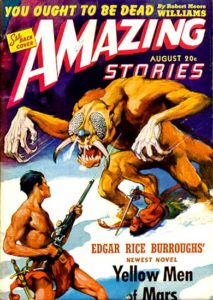

The first BEMs of the early pulps began with Edgar Rice Burroughs and his Barsoom series. The Tharks, or Green Men of Mars, have large eyes. Their pets, the dog-like calots, do also. But the Martian prize goes to the Apt, a weird cross between polar bear and insect, with its fly-like eyes that see everything. Burroughs wanted to suggest the alien and unusual so he often combined parts of different earthly creatures to achieve this effect. Burroughs was the single most influential sf writer after H.G. Wells.

In 1930, there were three science-fiction magazines (though they were known as scientifiction, a quaint term created by Hugo Gernsback): the original, Amazing Stories, begun in 1926; Science Wonder Stories, Gernsback’s second attempt after losing control of Amazing Stories; and the newcomer as of January 1930, Astounding Stories of Super Science, from a new editor in the field, Harry Bates. It is this last one that is usually accused of BEMism. Let’s look at three magazines from 1930 to 1938 (the coming of Campbell and the Golden Age of Science Fiction).

Amazing Stories had started off with the tech-loving art of Frank R. Paul — though Paul did do one cover with a giant fly for “The Eggs From Tanganyika” (July 1926). But when Gernsback had his magazines sold out under him, Frank Paul went with his former employer. T. O’Connor Sloane, Hugo’s old assistant, was now editor, and he established Leo Morey as the cover artist. Morey’s muddy covers were not a hit with fans though this may not have been his fault as Gernsback had cut costs with three-color processing. Despite the downgrade, no BEMs appeared on these covers.

Frank Paul did all the covers for Gernsback’s new competition, Air Wonder Stories and Science Wonder Stories. Later these two would be combined as Wonder Stories. Paul’s covers were almost exclusively large air or space ships, or Transformer-size machines. Occasionally he did people using amazing new inventions. The one cover featuring a monster (January 1930) has a gigantic tentacled thing occupying a glowing ball that might be a machine. No BEMs here either.

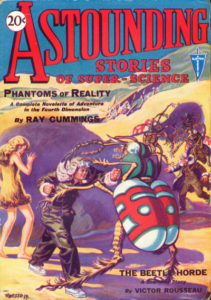

That leaves us with Harry Bates and Astounding. The premiere issue featured Victor Rousseau’s “The Beetle Horde” about a scientist who enlarges insects and then unleashes them on the world. The cover showed a brave hero punching a giant beetle. The creature has large fly-like eyes. In the background, a heroine dressed in a fur dress stands by watching in surprise. Here at last, our BEM!

The cover was by H. W. Wessolowski (known as Wesso). He would paint all 34 covers for the Clayton Astounding (from January 1930 to March 1933). The next six issues after that premiere BEM, all feature Frank R. Paul-like vessels and devices. April 1930 illustrates R.F. Starzl’s “Planet of Dread” with its one-eyed alien and a giant-eyed monster attacking him. This cover certainly qualifies, though no women are involved this time. September 1930 illustrates Paul Ernst’s “Marooned Under the Sea” with its desperate humans fighting off sea-dwelling tentacle creatures with, you guessed it, big eyes. And that’s it for 1930. Three BEMs for the first year.

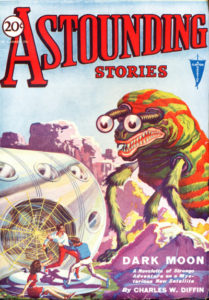

1931 has three covers again with a large-eyed squid in “The Tentacles From Below” (February) by Anthony Gilmore (Harry Bates and Desmond W. Hall) and big eyes on stalks can be seen with “Dark Moon” (May) by C. W. Differin and “The Red Hell of Jupiter” by Paul Ernst (October) with its balloon-headed aliens. 1932 and 1933 don’t really have any BEMs. This could be partly because the magazine was having trouble and only produced 10 more issues. “The Raiders of the Universes” by Donald Wandrei (September 1932) has a weird alien but its eyes are not prominent, and “The Coming of the Shining Ones” (December) by Hal K. Wells features a white alien with a large red spot but I don’t think this is an eye. By the middle of 1933 the Clayton chain was done and the magazine was sold to Street & Smith. The editor became F. Orlin Tremaine, who evolved the genre with his “thought variant” stories. In 1938, his assistant, John W. Campbell would take over, and Astounding would become the premiere sf magazine. The Golden Age had arrived, and no BEMs need apply.

Let’s do the math: the Clayton Astounding published 34 issues of which six had BEMs. That’s only 17.64 percent, or about 1/6th. Gorillas appeared on three covers, and humanesque aliens or robots on as many. Most prominent of all are spaceships and technology.

So why the idea that the Clayton Astounding was the domain of the BEM? I think this prejudice isn’t about cover art but a general dislike of the magazine contents. Lester Del Rey calls it “a sadly mixed business,” meaning not much sf but largely fantasy and horror. And at first this may be true, but as the magazine progressed it developed its own brand of sf tale, where the hero is always handsome, the girl beautiful, the aliens evil, and the exciting ending victorious. (One of the few exceptions to this was Lilith Lorraine’s “The Jovian Jest” [May 1930], a friend of H.P. Lovecraft, she shared his bleak approach to sf.)

Harry Bates, quite by accident, changed science fiction as much as Gernsback, Tremaine, or Campbell. (Some would say for the worse.) As part of the Clayton chain, Astounding was seen as an adventure pulp as much as any of their other magazines. It was not the Vernian herald of the future that Gernsback proposed. It was an adventure magazine set in space or in the future. It was about action. Action requires opposition, so Astounding was filled with opponents: diabolical Asians, crocodilian aliens, dinosaurs, space pirates, invasion fleets, and, of course, the bug-eyed monster.

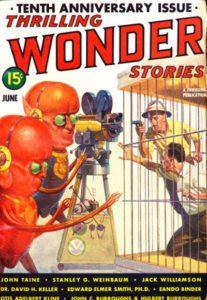

The Clayton Astounding was not the last of the juvenile-oriented sf adventure pulps. Its successor was Thrilling Wonder Stories, starting August 1936. Gernsback folded again. His Wonder Stories was sold to Beacon Magazines, a chain that featured the word “Thrilling” on many of their publications. So Wonder Stories became Thrilling Wonder Stories. And it was aimed at young readers. So much so that the editor was teen-age Mort Weisinger, and the magazine actually featured a comic called “Zarnak” (sin of sins!). And the covers featured the occasional BEM. The premiere issue has an alien with very large eyes. The second issue (October 1936) features a snaky critter with big eyes. June 1939 has large, bulgy aliens with big eyes filming human captives in a zoo; December 1939 has a giant fly attacking a skyscraper (shades of July 1926); February 1940, August 1940, January 1941, March 1941, February 1943, June 1943, Spring 1944, February 1948. … Other magazines such as TWS’s sister magazine, Startling Stories, were not BEM-less either.

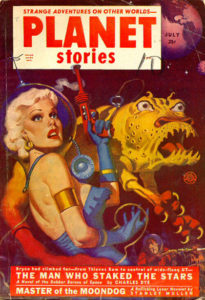

The idea that BEMs attack luscious space ladies comes more from this era, with the paintings of Earle Bergey for Thrilling Wonder. Every later cover features a space chick in danger (with or without a BEM). The Clayton Astounding did not feature many females after that first “Beetle Horde” cover. Perhaps my favorite of all BEM covers belongs to Planet Stories, another pulp that featured its share of space chicks and BEMs. While Campbell was revolutionizing sf, Malcolm Reiss created a pulp that made no apologies for its adventure slant. Starting with an Alexander Leydenfrost cover of Spring 1942, others followed: Summer of 1944, Fall 1944, Summer 1945, and July 1952’s “Master of the Moon-Dog” by Stanley Mullen sees the BEM as pet. We have come full circle, back to Edgar Rice Burroughs.

Good science fiction after 1938 claims to have no place for the bug-eyed monster, but this really isn’t the case. If we consider all the famous sf aliens of recent decades, we have Frank Herbert’s giant worms of Dune, not bug-eyed but certainly in spirit the same. (Self-righteous sf critics love to ignore the space-opera elements of the Dune novels.) We have the H.R. Giger alien from the Alien movies, in fact a no-eyed alien, but still a fraternal member of this club, descended from the very buggy bad guys of Robert A. Heinlein’s Starship Troopers (1959) and A.E. van Vogt’s “Discord in Scarlet,” a 1939 card-carrying member of the Astounding Golden Age. There is David Gerrold’s Chtorr series for a more recent example.

Science fiction likes to poke fun at the BEM in stories like “How Bug-Eyed Was My Monster” by Robert Bloch (Casper Magazine, May 1957), and “I-c-a-BeM” by Jack Vance (Amazing Stories, October 1961), and in anthologies like Mike Resnick’s Shaggy BEM Stories (1988) collecting stories that mock 1930s fiction including sword & sorcery, sword & planet, the Cthulhu mythos, as well as space opera.

That being said, the weird alien creature, with or without large bulging eyes, can be seen throughout sf, from Doctor Who to Star Trek to Star Wars, from the planets Yuggoth to Barsoom. It is part of our sf toolkit, our heritage, our dreams and nightmares. How bug-eyed was my monster? Very bug-eyed, indeed!

In closing I want to thank G.W. for a most intriguing look at the BEMs we all so lovingly remember. If you don’t feel motivated into picking up one of those stories and sitting down to read it tonight… well, you aren’t the pulp fan I thought you were! Bug-eyed monsters? That’s pulp!

Some years ago, a documentary titled “The Man who Painted Bug-Eyed Monsters” debuted. But it wasn’t about pulp artists; it was about 1950s poster artist Reynolds Brown, who depicted many a BEM for sci-fi movie posters.

Naturally I had to google it. The 1994 documentary is available on YouTube split into four segments, each of about 15 minutes. I’m definitely going to have to watch it.

I see there’s a book out, as well. “Reynold Brown: A Life in Pictures” by Daniel Zimmer and published in 2009. Available, used, for $300. Uh… er… I think I’ll stick with the film documentary.

Very good article. Lots of stuff that was new to me. A good fun read. Boy am I rambling…

It’s amazing how much there is to learn about this hobby and its related areas. And I’ve only scratched the surface, it seems.

Coincidently, last month’s Analog magazine had this to say “This is a term, by the way, that can be traced to Astounding—specifically, the cover illustration for Charles W. Diffin’s “Dark Moon” in the May 1931 issue.”