I have a confession to make: I only recently read “Tarzan of the Apes.”

Believe me, I tried to read it several times — back in high school in the ’70s, again sometime in the ’80s, and another time still — but I could never get past the first chapter or two.

Believe me, I tried to read it several times — back in high school in the ’70s, again sometime in the ’80s, and another time still — but I could never get past the first chapter or two.

I finally decided I needed to read one of the most famous pulp characters. So I revisited Tarzan. And I’m glad I did. I enjoyed the first book so much that I quickly picked up the next three novels in the series.

I flew through each of the first three adventures — “Tarzan of the Apes,” “The Return of Tarzan” and “The Beasts of Tarzan” — in just a couple of days each. But the fourth, “The Son of Tarzan,” proved to be a completely different beast.

Putting aside the fact that the whole idea of Tarzan stretches plausibility — hey, that’s what makes many pulp stories entertaining and why we read them, isn’t it? — the fourth novel pulls and twists plausibility past the breaking point, and brings all of Edgar Rice Burroughs‘ storytelling flaws into sharp focus.

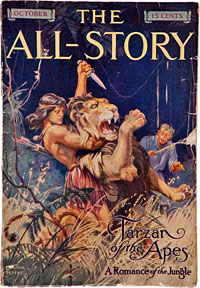

The initial novel, originally published in All-Story Magazine in October 1912, introduces us to John Clayton, the new-born son of Lord and Lady Greystoke, the loss of his parents, his upbringing by apes, and his becoming Tarzan (or “White Skin,” to the apes).

Midway through the book, we meet up with a number of characters who will return in subsequent stories: Jane Porter; her professor father, Archimedes Q. Porter; his assistant, Samuel T. Philander; Jane’s stereotypical black maid, Esmeralda; and French Lt. Paul D’Arnot, who becomes Tarzan’s close friend and introduces him to the civilized world.

(Since this is a review instead of a summary, I won’t go into detail about the books. You can read chapter-by-chapter summaries of them over at ERBList.com’s Edgar Rice Burroughs Summary Project if you wish. Or, better yet, read the books.)

“The Return of Tarzan” (originally serialized in New Story Magazine from June through December 1913) adds a couple of good-for-nothings — Nikolas Rokoff and Alexis Paulvitch — to the on-going cast, as well as introduces the lost city of Opar.

The third novel, “The Beasts of Tarzan” (All-Story Cavalier Weekly, May 16-June 13, 1914) continues the Rokoff/Paulvitch story and adds two new friends of Tarzan: Mugambi, chief of the Wagambi tribe, and Akut the ape.

“The Son of Tarzan” (All-Story Weekly, Dec. 4, 1915-Jan. 8, 1916) adds two key characters to the series: Jack Clayton, Tarzan and Jane’s son who adopts the name Korak the Killer; and Meriem, the kidnapped daughter of French military officer and prince.

“The Son of Tarzan” (All-Story Weekly, Dec. 4, 1915-Jan. 8, 1916) adds two key characters to the series: Jack Clayton, Tarzan and Jane’s son who adopts the name Korak the Killer; and Meriem, the kidnapped daughter of French military officer and prince.

Burroughs wasn’t a great writer, but he had a tremendous imagination and could tell a good story. He vividly depicts the Africa of his mind, a romanticized place where the difference between evil and good is black and white (quite often literally) and man can live alongside the wild beasts if he can revert to man’s ancestral animalistic tendencies.

Sure, no one ever spoke in the dialogue of Burroughs’ characters, but their long-winded colloquies do push the story along and provide background.

And too often events in the novels occur because of coincidences — shipwrecks, encounters between key characters, discoveries — rather than because of a character’s actions. This is never more evident than in “The Son of Tarzan,” which seems sadly to be built on a plot of coincidences.

I would hazard to guess that Burroughs spent more time writing “Tarzan of the Apes” than “The Son of Tarzan.” The fourth book seems very formulaic; we’ve read a lot of the events in the previous three books, but with different characters.

“The Son of Tarzan” was a long, hard slog for me. I finished it over three or four weeks, with breaks of several days. It ended predictably. And I can’t say it left me satisfied.

Maybe “Son” should be read in pieces; that’s the way it was originally read as a weekly serial. But I don’t think that excuses Burroughs.

Of the first three books, I would rank “The Beasts of Tarzan” a bit higher than “Tarzan of the Apes.” “The Return of Tarzan” would be an easy third. (Thinking back, I enjoyed “Beasts” the most.)

I’m taking a Burroughs break right now. But I’m interested in “Tarzan and the Jewels of Opar” (All-Story Weekly, Nov. 18-Dec. 16, 1916) and whether it’s better written than “Son.” So I’ll get back to it after a bit.