American pulp magazines weren’t the only sources for inexpensive escapism during the pulp era.

Let’s talk pulp heroes, you and me.

I only need two issues to complete my set of Rolf Torring, but those early 1930s issues are tough to find. I got a stack of Jan Mayen and Sun Koh in trade, a couple of dupes but. … huh? Really? Never heard of them? How about the Nyctalope? No? Zigomar? Vampires of the Air? Wow. Oh wait, I get it! You collect American pulps!

If you define what is or is not a pulp by the actual physical characteristics of the magazine — the slick cover stock, the fragrant, coarse paper, the size — then pulps are pretty much a uniquely American thing. Except for Canadian editions, even most of the foreign issues of American pulps are in a different format, with marginally better paper.

If, however, you define pulp by the type of fiction inside, then your world just expanded.

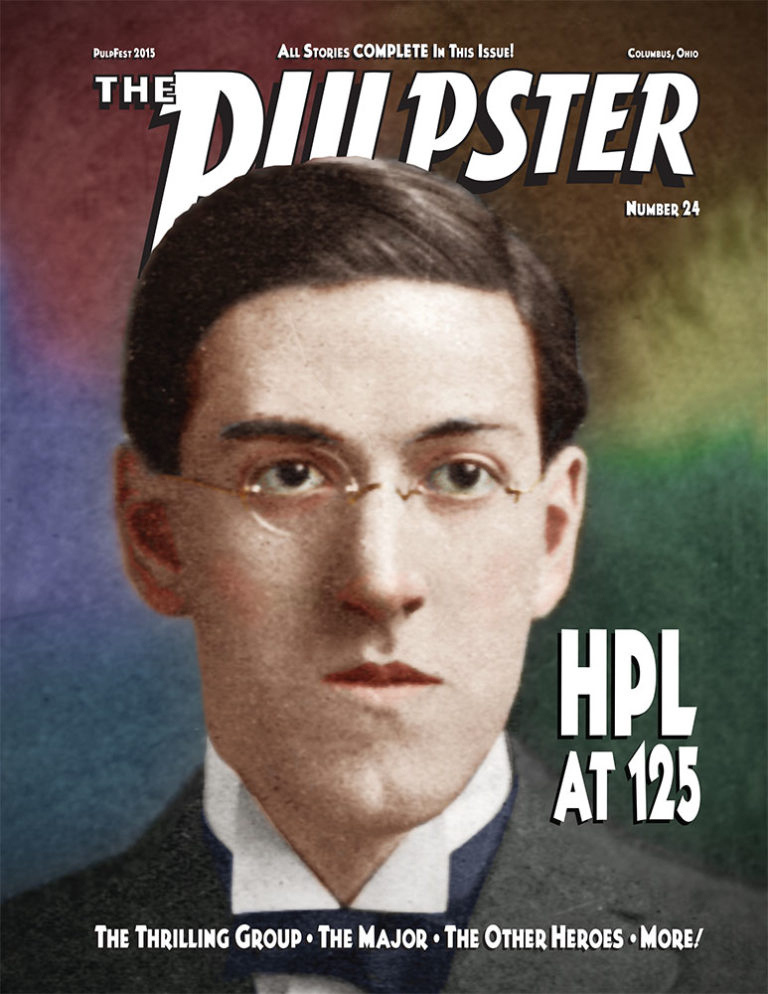

Fanzine flashback

This article originally appeared in The Pulpster (#24) for PulpFest 2015. Reprinted with permission.

This article originally appeared in The Pulpster (#24) for PulpFest 2015. Reprinted with permission.

Europe not only has a long, rich history of pulp fiction; in sheer volume it may even surpass our own here in the United States.

Our pulps grew out of the dime novel. The cheap, sensational fiction — and that’s not meant as a pejorative — was issued in various formats, starting with the story papers and booklet style novels, which melded into the black-and-white libraries and finally into the color covered weeklies that were the norm by the turn of the century.

Frank Munsey upset that apple cart in 1896 when he converted his Golden Argosy story paper to an all-fiction magazine printed on cheap wood-pulp paper, The Argosy. The fiction didn’t differ much from the contemporary dime-novel fare, but your 10 cents bought a lot more of it.

Still, it would take almost 15 years for the pulp format to really take hold, and another eight or 10 for the genre to really kick into gear.

Although there were always general fiction dime novels, toward the end the majority were the character weeklies: Nick Carter in New Nick Carter Weekly and Nick Carter Stories; Frank Merriwell and company in Tip Top Weekly and New Tip Top Weekly; Old and Young King Brady in Secret Service, etc.

As the pulp era got underway, the U.S. magazines reverted back to the variety style, even as they began to specialize in different genres. There were continuing characters, but it wouldn’t be until 1931, with the advent of The Shadow, that single character magazines would again find their footing.

A different path to pulp fiction

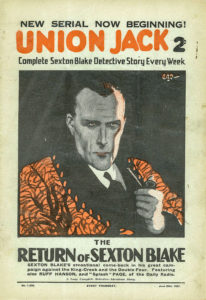

In Europe, the evolution was slightly different. Things never quite settled into a hard and fast format. In the early 19th century there were the equivalents of story papers in most countries, but there were also unique variations. English penny dreadfuls, serial stories issued in weekly penny parts, are the best known. These became the boys’ weeklies, such as Union Jack, The Wizard, and The Magnet, and produced major fiction characters such as Sexton Blake, Nelson Lee and Billy Bunter.

In France, the feulliton (newspaper serials) prevailed as the major venue, along with romans populaires, which were often collections of said serials. American dime novels like Nick Carter Weekly and Buffalo Bill Stories were translated and reprinted in the dime novel format, but the roman populaire existed right alongside them, chronicling the adventures of Fantômas, Zigomar and the Nyctalope. We’ll return to the first and third characters momentarily.

Germany was the real hotbed of early European pulpdom. The A. Eichler Co. was the first to translate American dime novels, starting with Nick Carter Weekly in 1906. Nick Carter was so popular that the stories would be reprinted and rewritten and reissued in almost every European country up to the 1940s, as would Buffalo Bill. But new stories were also written, as in the 1934 Italian series, Lord Lister contro Nick Carter (Lord Lister vs. Nick Carter). Lister is a Raffles-like character that first appeared in 1908; he appeared in over 1,362 stories up through the 1940s, and was being re-issued as late as 1968 — and that’s not counting the modern reprints.

In the 1920s, as the U.S. pulp magazine was starting its slow explosion, fiction publishers in Europe were pushing ahead with the old format. New pulpish characters sprang up like weeds throughout the decade.

Todd Marvel, Bob Wilson, Jack Dollar, and James Nobody were among the detectives keeping France safe, even as Fantômas, Mandrin, and Zigomar sought to destroy it. Fascinax dealt with supernatural threats, while the Nyctalope — he of the night vision and mechanical heart and quite possibly the world’s first superhero — fought evil geniuses on Mars and traveled through time to save his family. Although he first appeared in 1909, the Nyctalope’s adventures really got rolling in the early 1920s, and continued through the 1930s. After a several year pause, he came roaring back during World War II. Fantômas likewise continued his adventures beyond the 1930s; his final canonical adventure appeared in 1963.

Competition in the Weimar Germany was even fiercer. Harald Harst battled through 372 threats to humanity in Der Detektiv between 1919 and 1934; Frank Allan, der Rächer der Enterbten (Avenger of the Disinherited) started on the first of 672 adventures in 1920, and his adventures were reprinted all over Eastern Europe into the 1930s. The real-life film star Harry Piel continued his adventures in almost 300 issues of his own magazine, subtitled “the King of Adventurers and Despiser of Death.”

Though less successful, Jack Nelson vom Tric-Trac-Tric (…of the Tric-Trac-Tric) was essentially Judge Dredd, fighting crime and corruption in a future dystopia. Jim Buffalo, Der Mann mit der Teufelsmaschine (the Man With the Devil Machine) used said machine — the Supercar of its age, able to even travel through time — to fight crime on land, under the sea, and across time. While Sir Ralf Clifford, Der Unsichtbare Mensch oder Das Geheimnisvolle Vermächtnis des fakirs (…The Invisible Man or The Mysterious Legacy of the Fakirs) used the gift bestowed on him by an Indian fakir — the severed head of a cobra that bites Clifford and thus grants him temporary invisibility — to fight vampires and secret cults for 192 issues.

Phil Morgan – Der Herr der Welt (… Ruler of the World) used his superpowers, his mastery of science and his omni-vehicle, the Phaenomen-Apparat, to dispense justice amongst mad scientists and lost races alike for 171 issues. Baronet Duncan donned a domino mask in his continuous fight against a criminal gang.

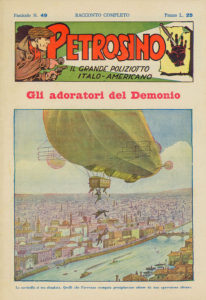

Italy wasn’t taking a back seat. Throughout the 1920s and into the 1930s, in addition to the numerous reprints of Nick Carter, Nat Pinkerton and others, home-grown titles such as Giusseppe Petrosino (a real life policeman who had taken on the Mafia), Ricimero Il re della Truffa (… King of the Swindle), Mister John Palmer, Capo del Club dei Sette (… Head of the Club of Seven) and William Mackbey, Il Poliziotto Giustzeiere (… the Policeman Executioner) took care of crime and general world adventuring, while Buck Taylor, il Terrore delle Pellirosse (… the Terror of the Redskins) and Fortebraccio, Lo Scotennatore di Pellirosse (… the Scalper of Redskins) cleared the American West.

Neither France nor Germany ignored the American West, though aside from the ubiquitous Buffalo Bill, the 1920s were a period of relative quiet. That wasn’t the case in the rest of Europe. Texas Jack (known in some locales as Kansas Jack), Sitting Bull, and other Indian chiefs raised heck in the years prior to the Great Depression in Brazil, Czechoslovakia, Croatia, Denmark, Finland, Poland, Portugal, and Spain. They’d find greater popularity after the crash.

In Britain, pulp fiction found its home in the story papers: Union Jack (starring Sexton Blake), and The Thriller (crime stories by Edgar Wallace, Leslie Charteris, and others), and, as the decade turned, The Wizard, The Triumph, and many others joined the list. Most featured a variety of fiction, from westerns to science fiction, and were aimed at a slightly younger audience than the others mentioned here. Their success, though, is indicated by the fact that most of these ran over 1,000 weekly issues. Sexton Blake and Nick Carter battle it out to this day over which appeared in more stories, but both lead the list by a margin of a thousand or more.

Czechoslovakia gave us detectives Leon Clifton and Harry Ward, the pirates Capt. Flint and Capt. Blood. Will Morton, Dr. Morrison, and Fyrst Basil (the thousand-masked master) represented Denmark’s super-sleuths. Nick Fantom and Tom Atkins went adventuring for Hungary, and Professor Sfzinx did … whatever someone named Sfzinx does.

Normanden Willums, the adventurous gentleman, balanced the karmic scales as Thomas Ryer, Norway’s most dangerous criminal, was on the loose. Wily Recai, influenced by Arsène Lupin, and Tes Hmet, the Turkish Sherlock Holmes, protected Turkey’s perimeter. Poland had Joe Deebs (strongest person and fairest detective in the world), as well as silent serial star Elmo Lincoln, and Robert and Bertrand, the cheerful international thieves. Spain brought the world yet another Raffles rip-off in Lord Jackson, as well as the unfortunately named young adventurer Dick Hard and the extraordinarily named Rohn Barack, el rajo exterminador — the ripping exterminator.

The adventurer leaps ahead

As the 1930s dawned, tastes were changing. Detectives and exotic adventure stories remained popular, but the world adventurer was fast taking hold. The big guns were ready to make their appearance in Europe, just as in the United States.

Three years before Doc Savage appeared on the stands, Rolf Torring’s Abenteuer (Adventurer) was discovering lost cities, lost races, touring the South Seas, fending off telepathic Tibetans, and battling were-tigers and living mummies, as well as some more mundane murderers and thieves.

For 446 issues between 1930-39, the German Torring fought the good fight, or at least the good fight as filtered through an evolving fascist and Nazi ethos. After the war, the adventures were rewritten to excise the worst of the Nazi elements and continued to be issued in book form into the 1960s. As in America, there is a robust trade in back issues as well as reprints of the originals (called nachdruck or nostalgie druck).

Even more Doc-like was Sun Koh, Der Erbe von Atlantis (… the Heir of Atlantis). In the first story, he falls out of the sky onto a London street, befuddled with amnesia and with an unreadable map tattooed on his back. Large in stature, with burnished bronze skin, Sun Koh battles super-science with the aid of assistants of diverse talents, though his goal is ultimately restoring Atlantis and saving the world. Like Torring, his character was an outgrowth of the social and political elements of Germany at that time. Unlike Doc, Sun Koh took his Nietzschean Ubermensch role to heart. As Jess Nevins notes, “The theme of Sun Koh is eugenics, who will be the strongest and most fit to survive in the new age.”

There were 150 issues in Sun Koh’s initial run from 1933-36, and 110 in his rewritten 1949-53 incarnation. The Sun Koh stories have enjoyed a popular reprint career and he has even appeared in new stories as part of the new pulp movement.

Jan Mayen fought against super-scientists and world menaces with the use of his atomic airplane, all the while searching for his missing father. There were 120 issues of his own magazine between 1936-38. Uniquely, it was revealed over time that the Mayen saga was actually a sequel to Sun Koh’s adventures, and the heir to Atlantis appeared in the later stories to continue his own quest.

Torring, Mayen and Sun Koh were not the only heroes to thrill German readers during the 1930s. Weimar-era adventurer Frank Allan was briefly revived; Tom Shark found favor as a German Sexton Blake-type detective, with a run of 553 issues through 1939, many of the adventures firmly footed in the fantastic. John Kling managed less than half that number of adventures through the same period, a still respectable 215 issues; but ultimately, Kling proved to be the most popular of the German detectives, appearing in, according to Jess Nevins’ extensive research, over 1,000 stories in the 1920s, ’30s and early ’50s. Out West, Billy Jenkins, Tex Bulwer, and Bob Hunter sustained long runs into the late 1930s. Al Capone got his own magazine, complete with photo covers, for a brief time in 1932-33. And although not a Mountie, Alaska Jim found 226 excuses for adventure in the Canadian wilds.

Buck Taylor handled the Wild West for Italy’s readers over the course of the mid-1930s; Joe Petrosino, in several incarnations, handled the detective work.

Masked cowboys. Pirates. Invisible men and master hypnotists. Submarine captains and youthful adventurers. They are all present in the European corpus, some more successful than others. And need I say that I haven’t even touched on the myriad anthology and romance titles?

The European pulp fiction scene is only now starting to get scrutiny, thanks to people like Jean-Marc and Randy Lofficier at Black Coat Press, who have brought excellent translations of the best of French pulp to the modern market; Jess Nevins, an obsessive researcher in the footsteps of Bleiler and Moskowitz; and Rimmer Sterk, collector and historian.

If the characters haven’t had the world impact of Doc Savage or The Shadow or The Spider… well, it ain’t over yet.

About the author

Larry Latham was an animator, artist, producer, and director. He created the webcomic “Lovecraft Is Missing” (archived) in 2008. Larry passed away in 2014 at age 61.