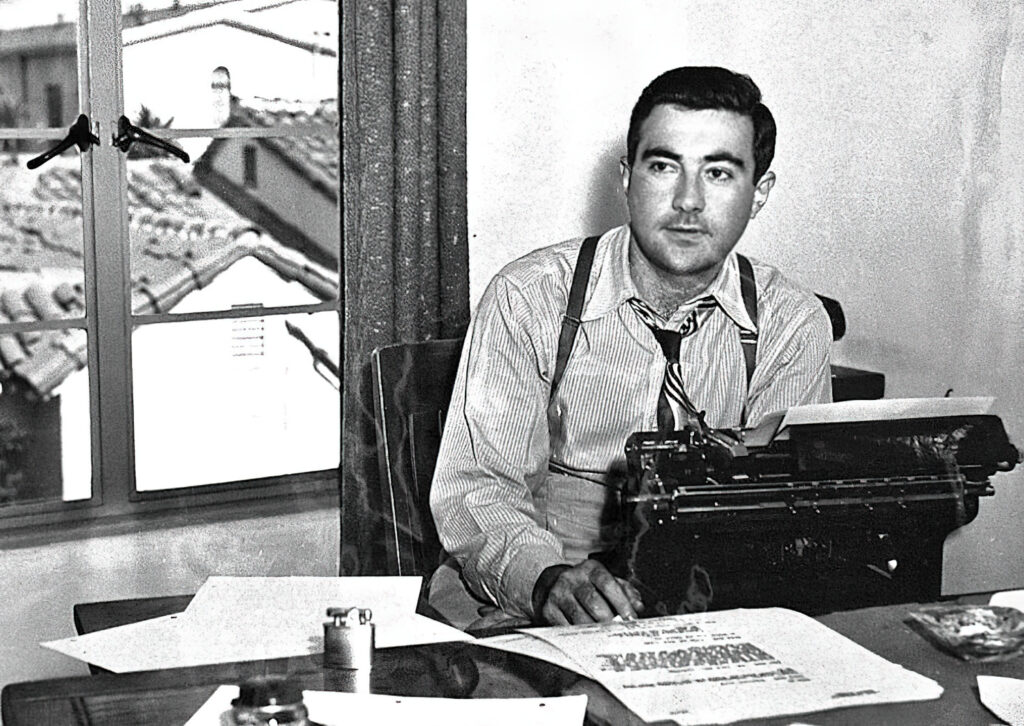

In a short burst of productivity, the writer filled the pages of pulps such as ‘Fighting Aces.’

Author David Goodis produced 17 novels between 1939 and 1961, plus one published posthumously in 1967. As a young man he wanted to create serious literature but is best remembered today for a series of 1950s noir paperbacks set in the seamy Tenderloin district of his native Philadelphia.

Admittedly, Goodis’s later novels are an acquired taste. To a coterie of enthusiasts, they are the work of an unsung genius, “America’s poet laureate of the low life.” To others, they are depressing accounts of marginalized losers spiraling downward in the squalid underside of America. Whatever you may think of them, it’s a stretch to realize they are the work of the same man, writing under a bevy of names, who once produced hundreds of upbeat formula stories for the western, mystery, sports, horror, and aviation pulps of the 1940s.

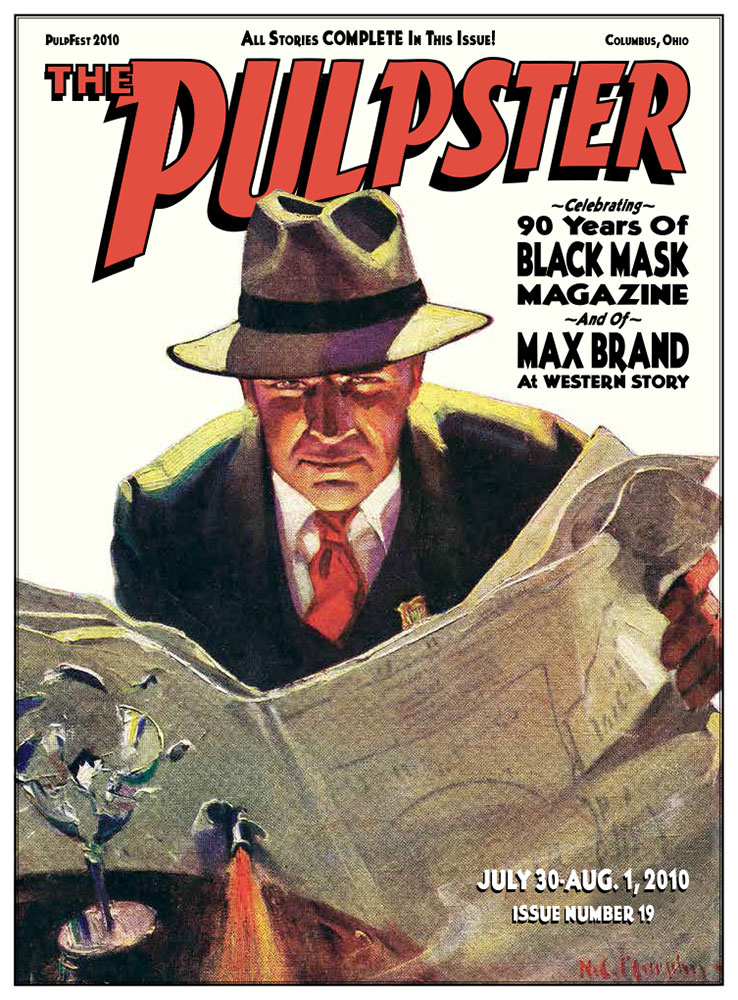

Fanzine flashback

This article originally appeared in The Pulpster (#19) for PulpFest 2010. Reprinted with permission.

This article originally appeared in The Pulpster (#19) for PulpFest 2010. Reprinted with permission.

In author Frederik Pohl’s guest of honor speech at the 1992 Pulpcon in Dayton, Ohio, Pohl discussed his days as an editor at Popular Publications. I believe he surprised many of us when he related: “The entire fiction content of every issue of Fighting Aces was supplied on contract every month by a young Californian named David Goodis. The stories appeared under endless pen names, but they were all the same.”

What interested me personally is that I remember reading issues of Popular’s Fighting Aces and Dare-Devil Aces back in the heady days of World War II and still recognize author names such as David Goodis, Lance Kermit, Ray P. Shotwell, David Crewe, and Logan Claybourne. What I didn’t know then was that they were bylines on stories written by a single individual.

The information is related in a collection of Goodis’s hard-boiled crime fiction titled Black Friday & Selected Stories, published in Britain in 2006 by Serpent’s Tail, London, and edited by Adrian Wootton.

In his opening introduction, Wootton contends that Goodis is “one of the great, unsung writers of the classic era of American pulp fiction.” He goes on to say, “Goodis said he wrote under seven names, including his own. I believe we have managed to identify three of the noms de plume pretty conclusively, i.e. David Crewe, Lance Kermit, and Logan Claybourne. I also think that he should have written under the moniker of Ray P. Shotwell. Of all the Goodis pseudonyms, it seems that Shotwell is definitely a house name, so it is difficult to establish what is and isn’t David Goodis.”

Under any name, it appears that David Goodis (1917-67) was one of the most prolific pulp writers of the 1940s. A native of Philadelphia, he began writing for the pulps even before his first novel, Retreat From Oblivion, was published by Dutton in 1939.

During the war years, he established himself as a reliable professional. Unlike most air-war writers, he had no flying experience whatever. According to his friends, he was a solitary, self-effacing man who lived in his own mind. He was a dedicated researcher who got his facts from standard aviation texts and dressed them up with fanciful adventures out of his imagination.

While air-war stories were his specialty, the aviation pulps were by no means Goodis’s only market. Within six years he claims to have sold 5.5-million words to a number of titles, with stories appearing in Popular Detective, Double-Action Detective, New Detective, Thrilling Adventures, Dare-Devil Aces, Battle Birds, RAF Aces, Fighting Aces, Dime Mystery, Sinister Stories, Terror Tales, Western Story Roundup, Detective Fiction Weekly, Big-Book Detective, G-Men Detective, Black Mask, Fifteen Western Tales, 10 Story Western, Sports Winners, Super Sports, Gangland Detective Stories, Wings, Sky Fighters, The Lone Eagle, and many others. He also produced scripts for radio series such as Superman, House of Mystery, and Hop Harrigan, America’s Ace of the Airwaves, all of which earned this writer’s loyal attention back then.

Goodis’s big break came in 1946 when his novel, Dark Passage, was serialized in The Saturday Evening Post and filmed by Warner Brothers starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall. He signed a six-year contract with the studio and set up residence in Los Angeles to serve an unsuccessful stint as a screenwriter. While continuing to write for the pulps he worked on a number of movie scripts, most of which remained unproduced. His only screenplay credit came on director Vincent Sherman’s The Unfaithful (1947), a disappointing low-budget remake of Somerset Maugham’s The Letter.

When Warners terminated his contract, Goodis returned to Philadelphia, broke and discouraged, to live with his aging parents and his mentally impaired brother, Herbert. There Goodis began churning out a series of cheap paperback originals set in the mean streets of his native city. These were all produced in the 1950s for Gold Medal and Lion at a time when paperbacks were replacing the pulps.

It must be noted that nothing could be more at odds with the heroic nature of pulp fiction than Goodis’s paperback noirs. It is almost difficult to believe that the same man once created stories with titles like “Bombs Over Burma,” “Hot Lead for Heinkels”, and “Guns of the Sea Raiders.” What attracted me to Black Friday & Selected Stories wasn’t the title novel (which has been reprinted previously) but the fact that the book is arguably the first and only collection of Goodis’s pulp short stories.

In his introduction, Wootton acknowledges, “The majority of his short fiction was written during World War II, when he would sometimes churn out whole issues of war story magazines under a variety of pseudonyms. … Nevertheless, in this collection, we have selected stories in the crime genre which is where David Goodis’s reputation rests.”

There are a dozen stories reprinted here, all examples of Goodis’s strong narrative skill: “The Dead Laugh Last,” written as David Crewe (Ten Story Mystery Magazine, October 1942); “Come to My Dying,” written as Logan C. Claybourne (Ten Story Mystery Magazine, October 1942); “The Case of the Laughing Queen,” written as Lance Kermit (Ten Story Mystery Magazine, October 1942); “Caravan to Tarim” (Collier’s, Oct. 26, 1943); “It’s a Wise Cadaver” (New Detective, July 1946); “The Time of Your Kill,” written as David Crewe (New Detective, November 1948); “Never Too Old to Burn,” written as Lance Kermit (New Detective, January 1949); “Man Without a Tongue,” written as David Crewe (New Detective, October 1951); “The Blue Sweetheart” (Manhunt, April 1953); “Professional Man” (Manhunt, October 1953); “Black Pudding” (Manhunt, December 1953); and “The Plunge” (Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine, vol. 3 no. 5, 1958).

What makes Black Friday & Selected Stories of special interest to pulp enthusiasts is that editor Wootton, with the participation of author/researcher Mike Ashley, has included a generous seven-page bibliography of Goodis’s pulp appearances under five names. There are 110 titles alone credited to his own name, 27 stories under the alias Logan Claybourne, 63 credited to David Crewe, 56 to Lane Kermit, and 38 written by Goodis lurking behind the house name of Ray P. Shot-well.

There would appear to be no single type of story or style to differentiate these names. It’s more likely that Goodis assumed several aliases to crowd as many of his stories as he could into single issues of magazines. (The first three stories reprinted in Wootton’s book, for instance, all appeared in the October 1942 Ten Story Mystery Magazine.)

Under his David Crewe pseudonym, Goodis is credited with 63 stories, of which 22 are air war, with others appearing in titles ranging from Black Mask to Western Story Roundup.

There are 27 Logan Claybourne stories listed in the bibliography, of which all but three are air war.

Aviation yarns constitute 44 out of 56 stories credited to Lance Kermit, with material in other magazines ranging from Adventure to New Detective Magazine.

Working under the house name Ray P. Shotwell, it appears that Goodis wrote at least 23 air wars with 15 other stories published in Big-Book Detective, New Detective Magazine, and 10-Story Mystery.

One thing that his bibliography proves is that Goodis never really “moved on” from magazine publication. Even though his most prolific output was in the 1940s, he continued to write short stories for the pulps and their successors over a long period. His first magazine publication came at the age of 17 (“The Shape of Murder,” Detective Fiction Weekly, Oct. 13, 1934) and his last just two years before his death (“The Sweet Taste,” Manhunt, January 1965). Despite his later fame for those downbeat paperback noirs and the movies based on them, it appears that he may be overdue for recognition as a significant contributor to the history of the pulp era.

In 1967, David Goodis died of a stroke at the too-young age of 49. Of the man himself, not much is known and much of what has been recorded appears contradictory. It is tempting to assume, as others have, that his paperback portraits of disgraced, out-of-luck outcasts form a sort of masochistic autobiography.

Personally, I prefer to believe they are works of fiction sprung from the imagination of the man who once wrote hundreds of high-flying aviation adventures without having set foot in a cockpit.

About the author

Lamont Award-winner Don Hutchison is a veteran pulp-era enthusiast who has produced five books on the subject, including The Great Pulp Heroes and Scarlet Riders. He was creator and editor of the acclaimed “Northern Frights” anthology series.