Churning out yarns for the pulp magazines wasn’t as cheery as the French Riviera, one hopeful fictioneer quickly learned.

I wrote in the pulps for six years.

I have no idea where or when some of my stories appeared, or even what name they might have appeared under other than my own or a reversal of my last name, T. Tennob, which I sometimes used. I remember that I once had the idea of using my own name on detective fiction, which was my favorite, another on sports, another on westerns or whatever.

I kept no records — the IRS not being in those days like it is now — and I kept almost none of the magazines in which my stories were printed. I was interested in the money I made, and the sight of my name in print never brought the thrill that some people say it is supposed to.

That was a long time ago, and I never gave those days a thought until the present wave of nostalgia got people talking about the pulps again.

I sold my first story in 1933. My last pulp story was in a Phantom Detective in 1939. This I know, because I happen to have a copy of it, which I dedicated to the fact that I never again was going to subject myself to the despair into which I plunged when a plot did not come easy or the words I wrote just didn’t seem right.

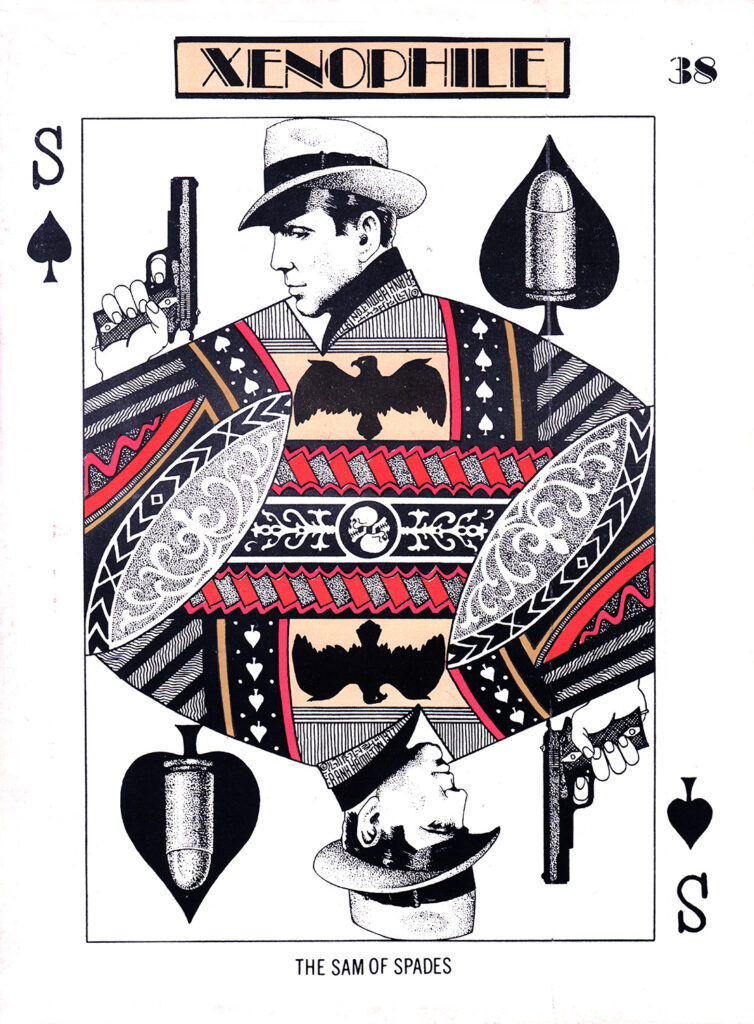

Fanzine flashback

This article originally appeared in Xenophile #38 (March-April 1978). It has been lightly edited.

This article originally appeared in Xenophile #38 (March-April 1978). It has been lightly edited.

I started writing because I needed the money, and I quit because my ship came in from an entirely different direction, and I knew I’d never have to touch my typewriter again to make a good living.

That last resolve didn’t quite last, but more about that later.

In 1933, the Depression was as bad as it was going to get, though it would continue at about the same pace for another half-dozen years. I was 20 years old, had a family, and an intense desire to keep a roof over our heads.

I had read the pulps from the time I was a kid, and I had a big thing for H. Bedford-Jones and J. Allen Dunn. They were rich. All authors were rich, and writing stories was an easy thing to do. You just wrote for a couple of hours each day and spent the rest of your time spending your money in the sunshine. I would become an author! A person could write on the Riviera as well as at his kitchen table back in Ohio.

I wrote a story and sent it to a magazine and waited for my check. I didn’t get one, but they were nice enough to send my story back because I had, at the last moment, enclosed a self-addressed, stamped envelope, not really thinking it would be used. It was a shock, and I remember that for some reason I felt humiliated, but it changed my attitude. I decided to learn something about what I was trying to do.

At the public library, I found there were magazines published strictly for writers. By the time I went through a few of them, I knew I could forget about the Riviera.

At the public library, I found there were magazines published strictly for writers. By the time I went through a few of them, I knew I could forget about the Riviera.

The writer’s magazines

These magazines devoted many pages to market tips, telling what the various publications wanted to buy, and what was being paid. I was crushed to find that there were entire chains of pulps that paid a half-cent a word for their stories, and that wasn’t on acceptance — it was on publication.

I found out later that there were editors among these cheaper pulps who would accept a story they liked even though they were heavily overstocked. If they held the story, it couldn’t be printed by the competition. After a year or so if the magazine went under without the story having been printed and paid for, what difference did it make? It could be returned to the author. So sorry!

Fortunately, most of the pulps paid from 1 to 2 cents a word, and they paid when the story was bought.

I also found from the writer’s magazines that most pulps were very rigid about story length. Some used shorts from 4,000 to 5,000 words, novelettes from 10,000 to 12,000. A 15,000-worder might be a novelette to one magazine and a lead novel to another.

There was one detective pulp, I remember, which insisted there be a murder within the first 500 words. Some wouldn’t consider a first-person story. There were pulps that wanted almost every story to have a lead character who could be carried through from issue to issue. Others wouldn’t use the same character twice. The list was endless.

I decided the logical thing to do was pick a few of the magazines I liked best and who paid at least a cent a word on acceptance. I would take their stories apart and see what made them go. Then I would slant my stories in that direction.

If the stories missed the intended market, then a round could be made of the other magazines, and hopefully one of them would buy the story. Of course, you always hoped the editor who bought it never found out he wasn’t the first one to whom it was offered.

It was a formula I used for six years, and it worked.

Eventually, Robert Thomas Hardy Inc. became my literary agent, and Eve Woodburn of that agency, a well-known writer herself, gave me a guiding hand and inspiration for which I was grateful. She spoke to me of the slick magazines and of the movies. She told me my writing was polished enough for the slicks and that I should try them.

It was one of the greatest ego boosters I ever had, but I was afraid to take the time. Five and 10 cents a word sounded great, but I knew the actual statistics were that only five new writers a year broke into the slick-paper magazines to stay. I didn’t have that much faith.

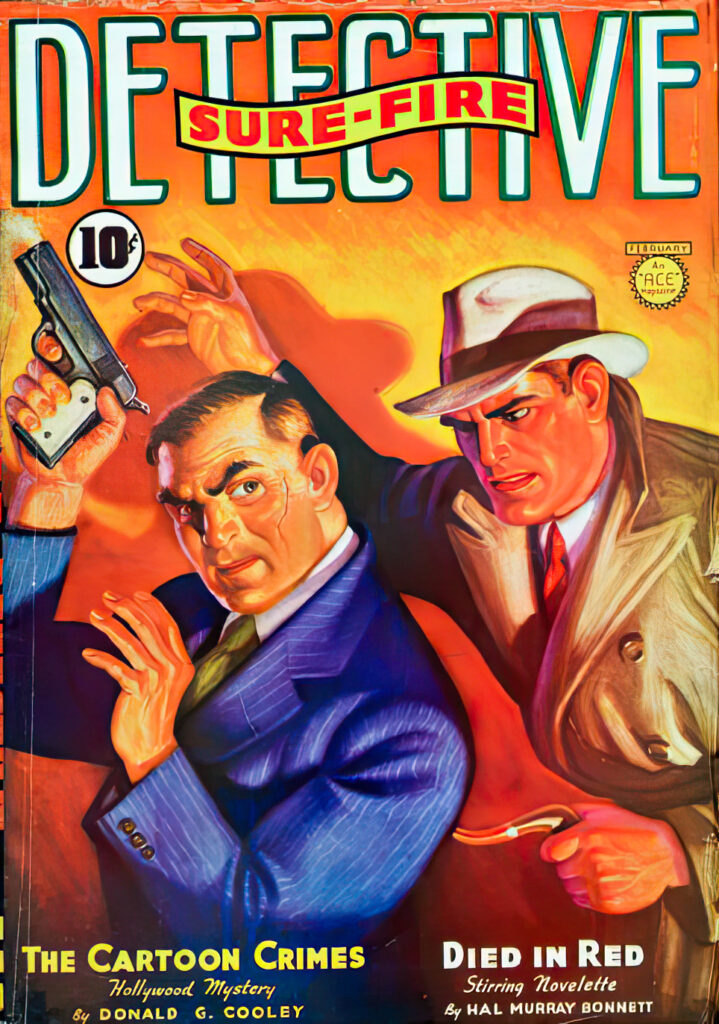

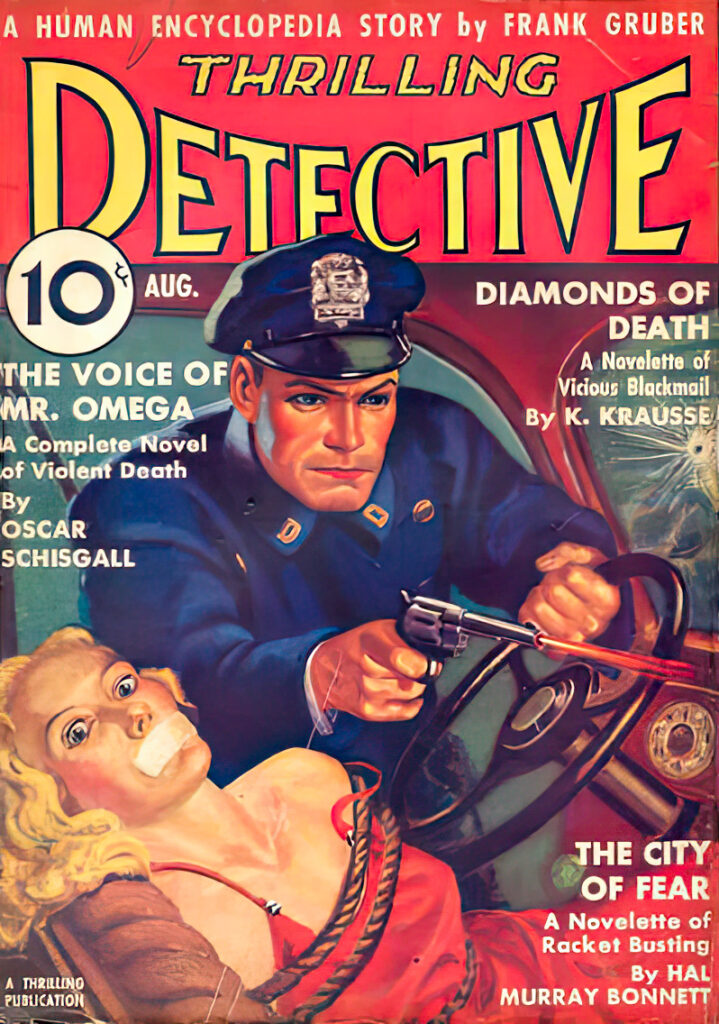

Meanwhile, I was selling F. Orlin Tremaine and John Nanovic at Street & Smith for their Clues and The Feds among others. I hit Detective Fiction Weekly. I got some nice letters from Joe Shaw. However, I never sold a story to Black Mask until Shaw was gone and Fanny Ellsworth took over.

Meanwhile, I was selling F. Orlin Tremaine and John Nanovic at Street & Smith for their Clues and The Feds among others. I hit Detective Fiction Weekly. I got some nice letters from Joe Shaw. However, I never sold a story to Black Mask until Shaw was gone and Fanny Ellsworth took over.

Effort vs. money

As I said before, it’s been over 35 years, and a lot of the memories have faded, but one little incident does come to mind that I think pretty well sums up the job of writing for the pulps.

I was entering the outer office at Street & Smith one day just as Steve Fisher came out of one of the inner sanctums.

Steve Fisher is one of the better of the pulp writers who went on to greater things. On this day his face was livid, and he was telling all who wanted to listen that some editors didn’t understand the problems of writers. I’m sure that Steve really knew that the editors understood the problems. They just didn’t give a damn!

One day I got word from Eve that an associate editor job was going to be open at Standard Magazines. Leo Margulies had told her he would consider me if I wanted the job. I thought now was the time to head for New York to live.

I had never actually met Leo Margulies before, though I had been appearing in his Thrilling line of books. He bounced up from his chair and shook my hand, a dynamic little man with a hair-line mustache and an air of being on the move even if he was sitting still. After a few moments of small talk, he got down to cases.

“Why,” he asked, “do you want this job?”

Something suddenly told me to do what I should have done before. Instead of answering his question, I asked one of my own: “Just how much does this job pay?”

“Twenty-five dollars a week,” he told me.

I knew then that I still belonged in Dayton, Ohio. So back I went — for good.

As I said, I never wrote for the pulps after 1939, but I did do a little more writing.

An unwanted film legacy

In the ’60s, a publisher friend of mine asked me to do several paperbacks for him, which I did, using a pseudonym. Eventually, he and some partners got ambitious and decided to produce a movie. He told me he liked my action stories and asked if I would I like to do an original story for them. A slam-bang, cops-and-robbers thing to be shot on the streets of New York. I said okay.

I wrote the story, which I titled “Satan in High Heels,” delivered it, and got paid. He liked the story. He was happy and I was happy.

I wrote the story, which I titled “Satan in High Heels,” delivered it, and got paid. He liked the story. He was happy and I was happy.

After the movie was well along toward being completed, I happened to be in New York, and I dropped around to see how things were coming.

I picked up a copy of the shooting script and glanced at it. Then I took a closer look.

“My God!” I exclaimed. “What happened?”

The producer shrugged his shoulders. “We decided that maybe this wasn’t the best time for another chase-type film. Art stuff is coming in. A few nude scenes. That sort of thing.”

I looked at the script again. “These characters — they don’t even seem to be the ones I wrote about.”

“They’re not. We did keep your title, though. Other than that the script writer just sort of winged it as we went along. Most people don’t really understand art movies, anyway.”

“Don’t put my name on it,” I told him.

“Too late. Even the record album of the music from the show has the jacket printed with your name as the author of the original story.”

The turkey did have a Broadway opening, but I don’t think anybody ever heard of it after that. If they’d used the story I really wrote, who knows?

Anyway, as far as movies are concerned, I’m glad I didn’t try harder in my younger days. I understand my experience is not unique.

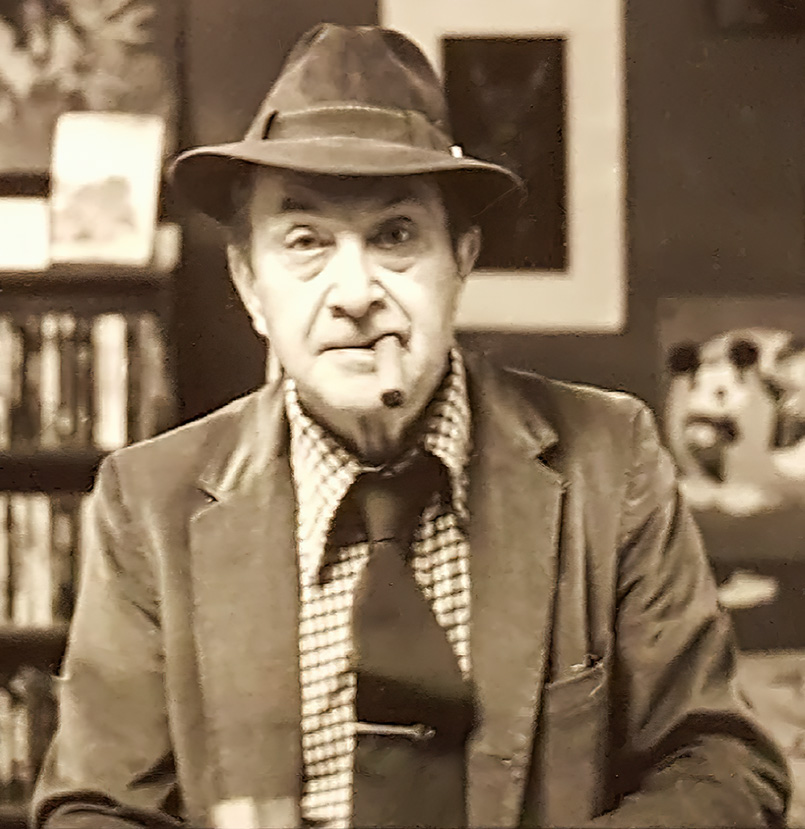

About the author

Harold Murray Bonnett’s short career as a pulp fictioneer was overshadowed by his lengthy ownership of Bonnett’s Books in Dayton Ohio. Many attendees at the Pulpcons held near Dayton remember the shop in the Oregon District. Mr. Bonnett died Nov. 3, 2005, at age 92. The store is still run by his family.