Analyzing Carroll John Daly’s hard-boiled novelette reveals why he was eclipsed by Dashiell Hammett.

1923 was a busy year. In America, Prohibition was swinging to the rhythms of jazz, a new style of music one commentator said “was the first step toward hell.” That hell was what F. Scott Fitzgerald called the Jazz Age. The carnage of World War I had convinced Americans that “all Gods were dead, all wars fought, all faiths in man shaken.” It was time to have fun, to forget the past, and, as the song said, “In the meantime, in between time, ain’t we got fun.”

In Europe, times were changing, too. Hitler tried to seize Munich’s city government. In Paris, Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, and other expatriate writers were creating a revolution in literature that would come to be known as “modernism.” Stateside in Manhattan, another literary revolution was taking place, not in the garrets of Greenwich Village but in a 128-page illustrated pulp fiction magazine called The Black Mask.

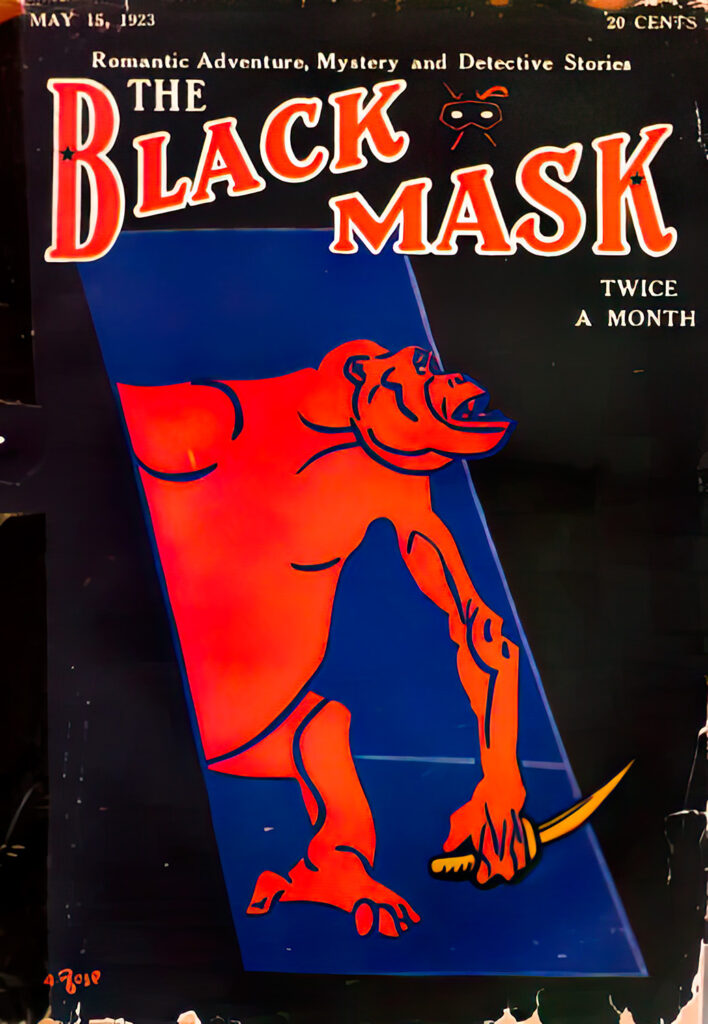

The Black Mask had been in circulation since 1920. Like all pulp magazines, The Black Mask “was about three things: action, adventure, and sex, not necessarily in that order.” In an era when literacy had never been higher, when the stock market was booming, the pulps enjoyed wide popular appeal. With their provocative titles, lurid covers, and racy illustrations, they were a cradle of sensationalism. Like television of today, the pulps were formula writing at its very best or, more often than not, its very worst.

Fanzine flashback

This article originally appeared in The Pulpster (#19) for PulpFest 2010. Reprinted with permission.

This article originally appeared in The Pulpster (#19) for PulpFest 2010. Reprinted with permission.

Then in May 1923, a story appeared in The Black Mask that would forever change pulp fiction and American culture as a whole. That story was Carroll John Daly’s crime novelette “Three Gun Terry.”

In the annals of detective fiction, “Three Gun Terry” is indeed a first. Terry Mack, the eponymous protagonist is, as William F. Nolan says, “the world’s first wisecracking, hard-boiled private investigator, the father of 10,000 private eyes who have gunned, slugged, and wisecracked their way through 10,000 magazines, books, films and TV episodes.”

With the publication of “Three Gun Terry,” subscriptions to The Black Mask soared. Terry Mack was a hit. At the height of the Jazz Age, Terry Mack, a character one critic describes as a “swaggering illiterate with the emotional instability of a gun-crazed vigilante,” was a piece of literary anarchy in a world in which anarchy reigned supreme. But the revolution wasn’t over yet.

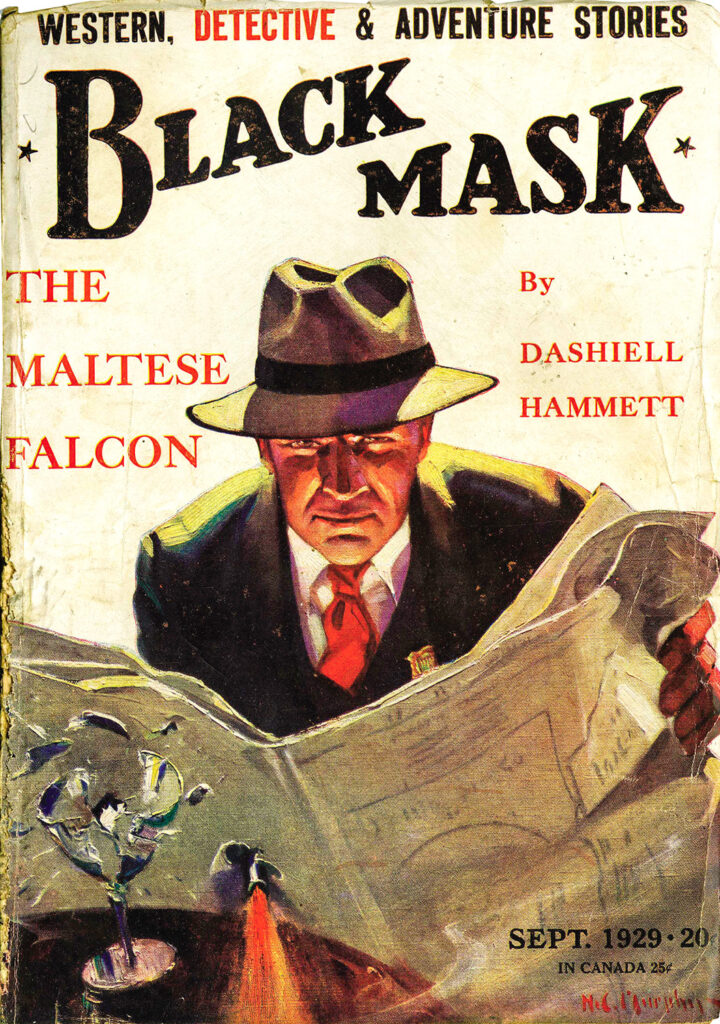

In October 1923, six months after the publication of “Three Gun Terry,” The Black Mask published a crime story by an aspiring writer named Peter Collinson. The title was “Arson Plus.” The hero was a nameless private eye who worked for the Continental Detective Agency. In time, the hero of “Arson Plus” would come to be known as the Continental Operative or simply “the Op.” “Arson Plus” was so popular Collinson decided to put his real name on subsequent Black Mask stories. That name was Dashiell Hammett, a name that would, over time, relegate Carroll John Daly and his seminal “Three Gun Terry” to literary obscurity.

Therein lies the question: Whatever happened to “Three Gun Terry”? Moreover, why has Carroll John Daly, a writer whom critics acknowledge as being the originator of an American literary icon — the hard-boiled private eye — why has his name fallen off the map while Dashiell Hammett has gone on to receive most of the credit for creating the genre of writing called hard-boiled crime fiction?

In answering this question, it’s important to remember what Raymond Chandler said in the introduction to his collection The Simple Act of Murder (1950):

Pulp (magazines) never dreamed of posterity. … It takes a very open mind to look beyond the gaudy covers, trashy titles, and barely acceptable advertisements and recognize the authentic power of a kind of writing that, even at its most mannered and artificial, made most of the fiction of the time taste like a cup of luke-warm consommé at a spinsterish tearoom.

A recluse writes

Carroll John Daly was born in Yonkers, N.Y., in 1889. After high school, he attended the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. He went on to run a movie theater in Atlantic City. In May 1923, when The Black Mask published “Three Gun Terry,” Daly was 33 and living as a recluse in White Plains, a suburb of New York City.

Why was Daly a recluse? Nobody knows. But we do know this: Rarely, if ever, did he venture into Manhattan, the setting for “Three Gun Terry.” Once Daly did make the trip into the city. When he returned home, so the story goes, he couldn’t find his house. A neighbor had to point it out to him.

Why was Daly a recluse? Nobody knows. But we do know this: Rarely, if ever, did he venture into Manhattan, the setting for “Three Gun Terry.” Once Daly did make the trip into the city. When he returned home, so the story goes, he couldn’t find his house. A neighbor had to point it out to him.

Once, for the sake of research, Daly decided maybe he should get to know what it was like to handle a gun. Daly bought a gun only to be arrested for carrying a concealed weapon. As one friend observed, “That was the end of Carroll John Daly’s research.”

Who then was Carroll John Daly? Think Walter Mitty, the James Thurber character. In life, Walter Mitty is your average Joe. In his dreams, however, he sees himself transformed. He is a romantic hero, battling bad guys and winning the day in the good old American way. Daly even admitted that at night, when he wrote, he became his alter ego, Terry Mack. For Carroll John Daly, that real-life alter ego could very well have been Dashiell Hammett. For in life, Hammett was everything Daly was not.

Samuel Dashiell Hammett was born in 1894. At 14, guided by “a rebellious temperament” he dropped out of school and went to work for the railroad. In 1915, at age 21, he joined the Pinkerton Detective Agency. As a Pinkerton operative, or “Op,” Hammett saw everything from petty theft to murder.

In 1918, Hammett left Pinkerton’s, joined the Army and contracted influenza. Soon after he developed tuberculosis. He left the army and went back to Pinkerton’s but poor health forced him to resign. In 1922, weakened by disease and in need of work, Hammett, encouraged by a friend, turned to writing. “He experimented with verse and short satiric pieces,” selling one to H.L. Mencken, editor of The Smart Set, the same high-brow “slick” magazine which “launched (F. Scott) Fitzgerald’s professional career.” Many believe it was Mencken who suggested that Hammett send work off to The Black Mask, a magazine Mencken once owned.

As aspiring crime writers, Daly and Hammett couldn’t have been more different. By 1923, Hammett had been around the block and then some, whereas Daly never left his house. Yet it was Daly who wrote “Three Gun Terry,” a shocking crime novelette that introduced Terry Mack, the world’s first hard-boiled private eye.

All this raises an intriguing question: If Daly had no experience of crime and cops, where did his stories come from? Was he such an inventive genius that he didn’t have to leave home to create a new literary form that transcended the need to draw from experience? I would argue not. The inspiration for Daly’s “Three Gun Terry” did not come from an inherent artistic genius that thrived on seclusion, or “being broke on the edge of the Sahara” as his bio claimed. It came from what he’d read, specifically late 19th-century dime novels and pulp magazines. It also came from the movies. In 1923, the most popular movies were romances, Westerns, and short gangster films.

There is no third-party evidence to prove what I have just asserted. As I said, Daly has been all but ignored by the critics. Why? Because despite creating a new fictional character, Daly nailed his creation, Terry Mack, to a plot employed by any number of 19th-century dime novels and early cowboy movies, a plot that has its roots firmly planted in the captivity narrative, a genre of writing that originated in New England, circa 1680.

Such an assertion opens the argument about experience and how it shapes a writer’s work — and who the hell am I to be taking pot shots at the origins of some guy’s art? But having read myriad late 19th-century dime novels, in particular Deadwood Dick, the most serialized cowboy hero after Buffalo Bill Cody, I quickly realized where Terry Mack was coming from, namely, the bedrock of the cowboy cliché, one of many such clichés which, when added up, have doomed “Three Gun Terry” to obscurity. Yet beneath all the clichés lives a character whose influence is still felt today.

As a novelette, “Three Gun Terry” is about 15,000 words. The first thing you notice is the title. It establishes an important fact: This story is not about a crime — i.e., “The Case of the Mutilated Foot” or “Corpse in a Cab” or “Body on a Slab.” It is not about where a crime took place — “Murder in the Rue Morgue,” “Murder Goes to College.” Nor is it about who got it between the eyes — “Monkey Sees Murder.”

Such title hooks were the hallmark of the detective story, circa 1870 to 1923. The title of “Three Gun Terry,” while not the first time a private eye’s name appears on the marquee, nevertheless reinforces what is new about “Three Gun Terry”: This story is about character.

It’s about character

Character. It’s what sets hard-boiled crime fiction apart from all other literary genres. Ironically, though, hard-boiled crime fiction is not about crime. Instead, hard-boiled crime fiction breaks the classic detective formula, the one in which a detective, through deduction, follows a series of clues to a climactic scene in which the crook gets his and justice prevails. In hard-boiled crime fiction, “crime, or the threat of a crime, (is) of secondary importance.” What’s important in hard-boiled crime fiction is character. Bill Pronzini, in Hard-boiled: An Anthology of Crime Fiction, describes just such a character.

The typical hard-boiled character is often a loner, a social misfit. He has a jaundiced view of government, power, and the world. If he is on the side of the angels, he is likely to be a cynical idealist: He believes that society is corrupt, but he also believes in justice and will make it his business to do whatever is necessary to see that justice is done. If he walks on the other side of the mean streets, he walks them at night; he is likely a predator, as morally bankrupt as any human being can be.

“A predator, as morally bankrupt as any human being can be.” That is Terry Mack. In the evolution of detective fiction, Terry Mack is considered the prototype, the original Terminator. Before Terry Mack, popular gumshoes such as Vidocq, Dupin, Sherlock Holmes, and Nick Carter could very well have been “swaggering illiterates,” but when push came to shove, they always came down on the side of the law. They were good battling evil, their actions an extension of a civilizing process, a return to order with good conquering evil.

Not so Terry Mack. The man is anarchy run amok, his most pronounced character trait: a chillingly cavalier, my-ethics-are-my-own attitude stamped onto a myopic worship of gunplay that sees violence as a means of solving any and all problems. Terry Mack is so addicted to gunplay, in fact, he spends more time bragging about his shooting prowess than he does solving the crime, namely, the kidnapping and subsequent rescue of “a virgin.”

My life is my own, and the opinions of others don’t interest me; so don’t form any, or if you do, keep them to yourself. If you want to sneer at my tactics, why go ahead, but do it behind the pages, you’ll find that healthier. So for my line. I have a little office that says TERRY MACK, Private Investigator on the door, which means whatever you wish to think. I ain’t a crook and I ain’t a dick; I play the game on the level, in my own way.

Notice how the story does not open with a plot hook, a body, or a crisis of some kind, all hallmarks of the detective story before May 1923.

Instead, “Three Gun Terry” opens with Terry Mack threatening the reader if the reader dares question Mr. Mack’s ethics. Sherlock Holmes would never stoop so low. But Terry Mack? Hell, he’ll kill you just as soon as look at you.

Therein lies the revolution: The detective story is no longer about solving a crime and seeing justice prevail. It is a question of ethics, of character.

Yet despite being a new literary figure, Terry Mack still has one foot planted deep in the past, his arsenal the most obvious clue to his literary origins. As the title indicates, Terry Mack carries three guns. Who in the annals of American fiction struts around packing so much iron? The cowboy-gunfighter, the archetypal loner with a pistol riding each hip and one up his sleeve just in case. That then is the image upon which Daly has modeled Terry Mack. And the best gunfighters are, as Terry Mack says, “the fastest on the draw.” This is not the mean streets of Manhattan. No. This is Dodge City.

Once you’ve got Terry Mack’s arsenal figured out you’ve pretty much got the man figured out. Like all gunfighters, he’s a rebel who follows his own moral code. The plot goes a long way in supporting this cowboy-as-cop metaphor. If you’ve seen Star Wars, The Searchers, or Mission Impossible III, you know the plot. If you’ve read The Last of the Mohicans or Le Morte d’Artur, you know it. If you’ve read any Nick Carter detective stories or Deadwood Dick or Seth Jones dime novels you know it. As far as plots go, it’s as American as apple pie. That plot is the captivity narrative, the first truly American narrative created by Mary Rowlandson, a New England Puritan. Rowlandson’s captivity narrative, A True History of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson, published in 1682, was the first best-seller in America.

Simply put, the captivity narrative pits good (civilized God-fearing whites) against evil (godless devils called Indians) with the white guys always coming out on top. This same plot is the hook upon which “Three Gun Terry” hangs.

A virgin, straight out of a convent, is kidnapped by gangsters (Indians always travel in packs). The bad guys hustle the virgin back to their hideout (Indian camp) where the virgin (bravely resisting) is threatened with red-hot pokers (standard implements of Indian torture) if she does not reveal “the secret formula” (that will destroy the world). By chance, Terry Mack witnesses the kidnapping, tracks the gang down, single-handedly storms the crooks in their lair, and saves the virgin. The rescued virgin worships her savior to no end, but Terry Mack, in another hard-boiled first, claims he is “off dames. They don’t go well with my business.”

Terry Mack’s misogyny is another first in detective fiction. Like many future hard-boiled dicks, Terry Mack wants nothing to do with dames. All they offer is love and stability, and if Terry Mack the loner-gunfighter fears anything, it’s being tied down. Why? Because he trusts no one.

This is another first in “Three Gun Terry,” the big city private eye riding a wave of unrelenting cynicism. It’s a theme that will echo all down the line, in Hammett’s “Arson Plus” and “The Maltese Falcon,” in Chandler’s The Big Sleep, in James Cain’s Double Indemnity, in Robert Towne’s screenplay Chinatown, and in Mickey Spillane’s I, The Jury, all classics of hard-boiled crime fiction.

His coal-black core

While the plot of “Three Gun Terry” does indeed lean on the tried-and-true, it’s Terry Mack’s coal-black core, defined through dialogue, that really turned the genre on its head. As the man himself says:

A fellow don’t have to take a shot at me to rouse my interest; you don’t have to give me a good moral reason to shoot. Show me the man, and if he’s drawing on me and needs a good killing, why, I’m the boy to do it.

One line bears repeating: “You don’t have to give me a good moral reason to shoot.” Pretty tame stuff, especially in this day and age. But viewed from a historical perspective, Terry Mack, a private eye in name only, has just put a bullet between the eyes of all his gumshoe forefathers. And he’s just warming up.

I ain’t a crook, and I ain’t a dick; I play the game on the level, in my own way. I’m in the center of the triangle; between the crook and the police and the victim.

In Terry Mack, that character is a cynical, self-serving moralist establishing a new archetype: the private eye as judge, jury, and executioner all wrapped up in one. Suspicious, alienated, cynical, gun-crazed, Terry Mack has all the makings of a truly modern man.

Yet, as evidenced by the plot, he still has one foot firmly rooted in the past, his cowboy twang adding another dimension to his literary pedigree.

Now, the city’s big, and that ain’t meant for no outburst of personal wisdom. It’s fact. Sometimes things is slow and I go out looking for business.

You can almost see the straw in his hair. Yet despite the giddy-up dialogue, Terry Mack is once again doing something brand new: He is looking for business.

In detective fiction of the day, the crime to be solved was literally in the first paragraph. Moreover, the cops or the relatives of the victim often enlisted an experienced detective to solve the case. In “Three Gun Terry,” such a scenario does not start the plot rolling. Instead, Terry Mack stumbles upon “a situation,” namely, the kidnapping of a virgin. Once involved, Terry Mack does something else entirely new. He doesn’t investigate a series of clues, as was the formula. Instead, he threatens his underworld connections with blackmail if they don’t cough up info about the virgin’s kidnappers. In other words, Terry Mack is using brawn over brains to solve a crime.

Raymond Chandler called this threat of violence, “the smell of fear.” Such a charged atmosphere is the hallmark of hard-boiled crime fiction, and Terry Mack, love him or hate him, started it all.

More importantly, the private eye, once the symbol of good, is now willing to murder to serve his own designs, for Terry Mack knows the virgin’s rescue will win him a sizable reward from her uncle. Best of all, the virgin knows the police commissioner who, in the end, exonerates Terry Mack for blowing away the bad guys. Terry Mack is not only “a gun-crazed vigilante,” but he’s also as lucky as an inside straight. Once again, pretty tame stuff. But remember: This is May 1923.

Detective formula turned on its head

With Terry Mack, Carroll John Daly has just turned the detective formula on its head. Suddenly, the private eye hero, the erstwhile symbol of law and order, is now an anti-hero, a predator in search of profit, a “swaggering illiterate” who will kill to get his way.

Yet despite such original moments, there remains something quirkily inconsistent about “Three Gun Terry.” Case in point: Before Terry Mack witnesses the virgin’s kidnapping, he can’t find any street action.

So it comes that things is slow. … Along about 1:30 (a.m.) I start for home — I got a car but I ain’t using it — the subway is my ticket that night.

Sorry, but try as I might, I can’t see Terry Mack, “a swaggering illiterate with the mentality of a gun-crazed vigilante” waiting in line to buy subway tokens, especially when he’s got a car.

But it doesn’t end there. Terry Mack has, of all things, a chauffeur-sidekick called “Bud.” If Terry Mack has a chauffeur-sidekick, why is he riding the subway? And why does Terry Mack persist in calling the virgin “Senorita” when she’s from Italy, not Spain?

“Three Gun Terry” is full of such incongruities. I call them Dalyisms. Why? One, because craft-wise this is just sloppy writing, and two, because a real private eye, a Continental Op, would not have a chauffer-sidekick. If he did have a chauffeur-sidekick, he sure as hell wouldn’t be riding the subway.

It’s pretty obvious what is happening here: Daly, the formula writer, is remembering what Daly, the reader, read, and what Daly read said that a hero always had a sidekick. After all, Sherlock Holmes had Watson, Nick Carter had Patsy and Scrubby, and Hawkeye had Chingachgook.

That was the formula and Daly, despite creating an archetype in Terry Mack, was, at the end of the day, a formula writer. He wasn’t writing about the mean streets. He was superimposing the Wild West on Manhattan, and the Wild West, according to the literature of the time, was full of bad guys who kidnapped and tortured virginal senoritas. In other words, Daly was giving the public exactly what they wanted: a story tried-and-true.

We can chip away at “Three Gun Terry” all we want, but one fact is beyond dispute: Terry Mack is the father of Sam Spade, Phillip Marlowe, Lew Archer, Little Caesar, Mike Hammer, Dirty Harry, Rambo, the Terminator, and all the computer games in which criminal anti-heroes blast away with impunity.

Listen to any piece of gangsta’ rap — Snoop Dogg, 50 Cent, Lil Wayne — and you will hear echoes of Terry Mack’s misogyny, his thirst for profit at any price, and his my-way-or-the-highway credo.

American culture has indeed cashed in on Carroll John Daly’s creation, the “swaggering illiterate” called Terry Mack, a character time has all but erased. Why? More specifically, why has Carroll John Daly, the acknowledged father of hard-boiled crime fiction, been all but forgotten while Dashiell Hammett is considered the pioneer of hard-boiled crime fiction?

“Arson Plus” was first published in The Black Mask in October 1923, six months after Daly’s “Three Gun Terry.” Being published in the same magazine so close in time one would think that “Arson Plus” would bear some resemblance to “Three Gun Terry.” After all, The Black Mask was all about money, and money meant formula writing.

And yes, on the formula front, “Arson Plus” does indeed end with a shootout much like “Three Gun Terry.” But other than that, these two ground-breaking crime stories are worlds apart.

Like “Three Gun Terry,” “Arson Plus” introduces a new character to the world of detective fiction: a private eye called the Continental Op. The Op investigates an insurance company’s claim that “a client torched a house.” Unlike Terry Mack, the Op doesn’t stumble upon “a situation.” Instead, the Op is all business.

From the get-go, he knows exactly where he’s going and, with help from the police, he moves assiduously from suspect to suspect until the arsonist gets his. By today’s standards, pretty routine stuff. Hammett was definitely following the formula. So where is the revolution?

As we know, hard-boiled crime fiction is all about character. In “Three Gun Terry,” Terry Mack continually lets us know he’s bad news, and proud of it. However, in “Arson Plus,” the Op does the exact opposite: He plays his cards close to his chest. He’s not a braggart or a self-serving moralist who enforces his own code of ethics at the point of a gun. We’re not even sure if the Op carries a gun. Not only that, but we don’t know what he looks like until halfway through the story. When the Op interviews a suspect, a beautiful young seductress who has kept him waiting, the Op feels a momentary attraction only to admit:

I was a busy middle-aged detective who was fuming over having his time wasted. I was a lot more interested in finding the bird who struck the match than I was in finding feminine beauty. But I smothered my grouch and got down to business.

“A busy, middle-aged detective.” That’s all we get. What does it imply? It implies, as Dorothy Parker says, that “Hammett (is doing) his readers the infinite courtesy of allowing them to supply descriptions and analyses for themselves.”

In other words, Hammett is letting us create our own image of the Op. And that image is everything Terry Mack is not. Where Terry Mack is young and gunning, the Op is older, slower. Probably smokes too much and needs a drink bad.

One thing is certain though: The Op’s character is defined by action. Terry Mack is also defined by action, but it’s pure fantasy. In short, Terry Mack is the same-old cavalry storming the same-old Indian village to save the same-old virgin in the same-old hail of bullets. The Op, however, pegged to Hammett’s concise prose, races us through a realistic world full of “stuttering witnesses and mundane police procedure” framing, curiously enough, a victimless crime.

In “Arson Plus,” we are not tagging along with the Op as we are with Terry Mack. Because the Op is nameless and faceless, we are the Op. We have created him in our own likeness by filling in the blanks of his character. Having done so, Hammett has allowed his readers to place themselves on the frontline of a stark new realism in detective fiction.

An Arthurian knight of the pulps

Like Terry Mack, the Op also harbors a healthy degree of cynicism.

However, Terry Mack’s cynicism can’t hide the romantic buried deep within. And the more he talks, the more his true character is revealed, for in damning both good and evil, he is not so much commenting on the world at large but rather massaging his own romantic view of himself. Moreover, Terry Mack might be “a swaggering illiterate” who follows his own moral code, but in rescuing the virgin, the symbol of innocence, he remains an optimist, an Arthurian knight who, underneath all the tough-guy talk, believes that justice will out in the end, which is exactly what happens. Order is restored; civilization is saved. In other words, Terry Mack is not half as new as he seems.

Compared to Terry Mack, the Op’s brand of cynicism is something quite different. As far as crime goes, the Op, much like Hammett himself, has “been there, done that” more times than he cares to recall. In this light, he is jaded to the core.

Working the mean streets has turned him into a cynic, a man who brushes beauty aside not because he hates dames, but because he has seen through the game of life and, more mundanely, he has a job to do. He is not a coked-out intellectual in a deerstalker cap. He is not a cowboy packing three irons and a my-way-or-the-highway ethic.

Instead, the Op is an everyman. He is on the side of the law not because he wants to do good, but because he is being paid to do a job, to find facts and right a wrong. In his search for the truth, romance is sacrificed at the altar of expediency.

Therein lies the revolution. In “Arson Plus,” the Op represents the death of romanticism in detective fiction. He is the sword rammed straight through the hearts of all the shining knights, the Vidocqs, the Sherlock Holmes, the Nick Carters, and even Terry Mack himself.

In “Arson Plus,” as in all of Hammett’s work, death is serious business, not grounds for romantic boasting. Not so for Daly.

Why did Daly pen such a cavalier approach to life and death? First off, as a formula writer, Daly knew what his audience wanted, and he delivered. Daly, safe within his suburban home, toyed with death because, unlike Hammett, he’d never stared mean-street death in the face.

Daly’s bio proves he had no experience of what it meant to be a working cop. In short, he lacked Hammett’s real-world perspective on what it meant to investigate a murder.

Some would argue that to judge what experiences shaped Daly’s writing is pure speculation thus no basis for an argument. That would be true if we were talking about a bona fide reclusive genius.

But there’s the rub: Daly wasn’t a genius. At his best, he was a formula hack who, drawing on a lifetime of influences, created a character, a crude prototype that other writers, beginning with Dashiell Hammett, would, in time, refine and transform into an archetype.

Meanwhile, “Three Gun Terry,” burdened by its predictable, captivity-narrative plot — a plot whose variations can be found in almost every late 19th-century dime novel and early movie — has failed to stand the test of time.

Suffice it to say, reading Daly’s “Three Gun Terry” and his later work is like watching repeats of The Terminator: great eye candy, but not much for the mind. Such an approach did make Daly a fast buck, but it did not breed great and lasting art.

Repeating plot and character clichés

Hammett, on the other hand, because he had worked the streets, because he had been an Op, presents us with a more realistic picture of police procedure starting with “Arson Plus.”

Hammett doesn’t need to tart things up with cowboy slang. He doesn’t need to lean on a time-worn plot to get from A to Z.

Moreover, his brand of cynicism has been forged on the frontline of experience. No big deal today, but back in 1923, the Op signaled the death of romanticism in the detective genre. The Op was, and still is, truly hard-boiled, a popular Jazz-Age phrase that means “without sentiment.” More importantly, the Op was real.

Stylistically, “Arson Plus” is so straightforward, so stripped of pretense it rivals Hemingway for clarity and simplicity. Read early Hammett and early Hemingway, and you’ll wonder who influenced whom.

Hammett, in “Arson Plus,” reveals “an aspiring writer’s intuitive command of formalist elements,” which forge a compelling new character called the Op. That is another reason why Dashiell Hammett has eclipsed Carroll John Daly as the father of hard-boiled crime fiction.

But there is another more salient reason why Dashiell Hammett is considered the creator of hard-boiled crime fiction. While Daly’s later work repeated the same plot and character clichés, Hammett was steadily evolving his craft. In time, he came to use the crime story as a vehicle through which he, as a writer, could comment on life itself.

We catch an awakening of this in “Arson Plus,” a moment in which Hammett is struggling to do more than just entertain. When the Op visits the torched house, he says, “(I) poked around in the ashes for a few minutes, not that (I) expected to find anything, but because it is man’s nature to poke around in ruins.”

With this sentence, Hammett draws a line in the sand. This is no longer pulp fiction. This is not another deducing detective. This is a writer rising above the limitations of his genre, an artist commenting, however briefly, on the nature of man who, by poking around in death, might find the key to the mystery called life.

All that from an aspiring writer first published in H. L. Mencken’s The Smart Set, Mencken being the same editor who first published F. Scott Fitzgerald; Mencken, the same critic who had previously rejected stories from James Joyce’s Dubliners and early work from Hemingway, while publishing work from an unknown writer named Sam Hammett.

All that from an aspiring writer first published in H. L. Mencken’s The Smart Set, Mencken being the same editor who first published F. Scott Fitzgerald; Mencken, the same critic who had previously rejected stories from James Joyce’s Dubliners and early work from Hemingway, while publishing work from an unknown writer named Sam Hammett.

“It is man’s nature to poke around in ruins.” Six years later, in 1929, this same line will define Sam Spade in “The Maltese Falcon.” Spade, like the Op, is poking around not in the ruins of a torched house but in a world of failed dreams.

Plot-wise, “The Maltese Falcon” follows Sam Spade, a private detective hired by a femme fatale seeking protection from a gang of miscreants. It turns out, however, that the femme fatale and the miscreants are in cahoots as they search the world over for a priceless statuette called the Maltese Falcon.

If found, the elusive falcon will make the gang fabulously rich. Metaphorically, the falcon is the Grail story and all it implies. Yet the miscreants, like Arthur’s knights, fail to find immortality. Frustrated, their dreams in ruins, the miscreants turn on each other. Therein lies the genius of Dashiell Hammett.

By analogizing the Maltese Falcon to the Grail quest, Hammett is using mythology to comment upon the deluding nature of man’s dreams, for the falcon, like the Grail, will never be found. It will always remain, as Spade says, “The stuff dreams are made of.”

This same theme is echoed in James Joyce’s “Araby,” a short story many consider the greatest ever written.

At the end of “Araby,” the boy-hero, having failed to find love at the fair, realizes the deluding nature of his dreams and, in turn, the deluding nature of romanticism itself. Joyce brings us to this epiphany — another seminal moment in literature — by using the same mythological, Grail-quest that Hammett employs in “The Maltese Falcon.”

“The Maltese Falcon” is considered the defining masterpiece of hard-boiled crime fiction. True to form, it packs a lot of tough-guy talk and gunplay. More importantly, it focuses on character, a jaded anti-hero named Sam Spade who comes to realize that the falcon is shielding the miscreants from a ruinous truth, the fact that life and the dreams upon which it is built, are an illusion of one’s own making.

Such a comment elevates “The Maltese Falcon” into the realm of existentialist inquiry, the miscreants and their quest a metaphor that asks the age-old question: What is the meaning of life?

Great literature is a study of character. Great literature transcends genre. For Hammett, that transcendence started in “Arson Plus” and was realized in “The Maltese Falcon.”

The arc of Hammett’s art is clear, whereas Daly never broke free of the mold.

Read any number of Daly’s later works and this will become abundantly clear. The closest Daly came to turning a phrase can be found in “Three Gun Terry.”

Waiting for the bad guys, Terry Mack says, “When I look out the window, that street is as deserted as a poetry graveyard.”

“A poetry graveyard.” Not a poet’s graveyard, mind you, but “a poetry graveyard.” A place where dead poems are buried, or so it seems.

It’s easy to poke fun at Carroll John Daly, too easy, but this awkward metaphor is, nevertheless, just another in a long list of Dalyisms that, when added up, conspire to overshadow Daly’s literary claim to fame: the creation of Terry Mack, the world’s first hard-boiled private eye.

An earlier version of “Whatever Happened to ‘Three Gun Terry’?” was first published in 2008 in The Back Alley, a webzine devoted to hard-boiled crime fiction.

About the author

Richard Bruce Stirling is a writer-filmmaker living and working in Cambria, Calif. He is currently writing a book on Hearst Castle. In doing so, he has come to realize that Carroll John Daly’s writing was very much influenced by William Randolph Hearst’s yellow journalism, a type of sensationalized journalism that read, as one writer said, like “a woman running down the street with her head cut off.”