April 8, 1949: The day the pulps died.

That Friday, Street & Smith Publications announced that it would stop publishing its line of pulp magazines. Within months, The Shadow, Doc Savage, Detective Story and Western Story — the last four of 40-plus pulp titles that Street had put out over 40-plus years — would disappear from the newsstands.

The final quartet, including the company’s longest-running pulp, Detective Story, which first hit the stands in 1915, vanished with their Summer 1949 numbers. (Detective Story and Western Story would return for short runs under Popular Publications’ imprint three years later.)

It wasn’t the first time a publisher halted pulp publishing. Companies such as Clayton and MacFadden had left the pulpwood business in the past. And pulps would remain on newsstands and arriving in mailboxes for a few years after Street’s announcement. But it wouldn’t be long before Dell, Fawcett, Wyn, Trojan and others followed Street & Smith’s lead. Street’s decision was, as The New York Times called it in an April 9, 1949, article, “the death-knell for pulp-paper fiction.”

Fanzine flashback

This article appeared in The Pulpster (No. 17, 2008).

This article appeared in The Pulpster (No. 17, 2008).

“They weren’t making any money,” Street president Gerald H. Smith explained to Time magazine. “We just weren’t interested in them any longer.”

Street was also losing interest in its comic books and canceled those, too, along with its pulps.

What Street was interested in then were its slick magazines, Mademoiselle, Mademoiselle’s Living and Charm. After an awkward start in 1935, Mademoiselle had taken off with its circulation reaching 300,000 by 1940 and over half-a-million by 1955.

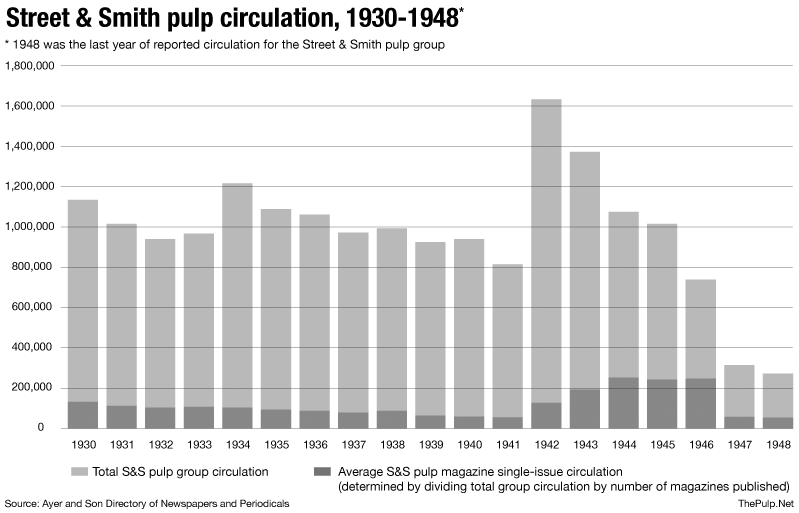

Like Street, readers, apparently, were losing interest in the pulps, too. Circulation figures for Street’s pulp group show a dramatic drop leading up to the company’s 1949 decision. Through the 1930s pulp heyday, Street’s pulp circulation hovered around a million copies a month, with a peak of 1.2-million in 1935.

As World War II heated up and the United States became embroiled in the global conflict, Street pulp circulation dropped 1940 through 1942.

As paper became scarce and the number of pulps declined on the newsstands, Street’s circulations soared to over 1.6-million copies in 1943. Remember the economic maxim about supply and demand: Fewer pulps meant better sales for the remaining magazines. “In all brackets, the pulps which had been losing popularity boomed in sales,” Writer’s Digest editor Aron M. Mathieu recalled in a 1951 Digest article. “Some people thought this sudden success was due only to the forced scarcity of magazines; but most older pulp editors felt it proved how right they had been all along. ‘The tide swings,’ they said. ‘The pulps always come back.’ ”

But circulation turned sour again as the war ended. Figures from 1944 through 1949 show fewer and fewer sales for Street’s pulp magazines. Time magazine blamed the decrease on “changing times and tastes…. Radio, television, and the newsstand competition of the 25-cent reprint books had shrunk the market.”

The New York Times reported, “The growing popularity of television is most frequently mentioned (as a factor in the decline of the pulps). Persons close to the field point out, too, that, in the case of the ‘pulps,’ readers have grown tired of the same ‘format’ and are turning to other types of fiction.”

Street’s chairman, Allen L. Grammer, agreed. “There has been a great change in the material offered at newsstands throughout the country. Picture books and reprints of books that normally would sell for $1.50 to $3.50 are now being made available to millions and at low prices,” Grammer told The New York Times.

But the change in the nation’s interests weren’t clearly foreseen by everyone.

In a satirical column, The New Yorker magazine poked fun at the pulp industry with a fake “interview” with Street vice president Henry Ralston, pointing out the pulp houses’ lack of innovation and tendancy to stick with whatever worked well in the past.

After a recap of Street’s canceled pulps, the “Talk of the Town” item recounts how Street & Smith published Horatio Alger’s first story, “Marie Bertrand,” in The New York Weekly in 1868. And how Street continued publishing Alger’s works until he died in 1899 — then continued to reprint his 180 novels until the 1930s.

The item builds until this zinger:

“Mr. Ralston is an unwritten Horatio Alger story himself. He was hired by Street & Smith as an office boy in 1898 and rose through the ranks to the vice-presidency. Gerald H. Smith, the present head of the firm, is a grandson of the original Smith, and it was one of Ralston’s most agreeable duties during the scion’s formative years to keep him supplied with pulps. Ralston has a full file of Alger books in his office and occasionally takes one home to read himself to sleep with. As we were leaving, he presented us with a copy of ‘Ben’s Nugget, or, A Triumph of the Right.’ ‘Why these Alger books stopped selling is incomprehensible to me,’ he said.”

In an article in the Writer’s 1951 Year Book, fictioneer Allan K. Echols echoes this sentiment. “Pulp editing hardly changed for 30 years; yet compare Ladies’ Home Journal, Vogue, Wall Street Journal, Saturday Evening Post today to 1915! These magazines changed artistically and editorially as people’s minds expanded with the store of more information.” Pulps, he goes on, didn’t.

The pulps’ eminent demise remained unforeseen even to other fictioneers. Articles in writer’s magazines continued to suggest that, sure, things weren’t so great with the pulp market, but they would get better.

Jack Byrne, managing editor for Fiction House, replied to Echols in a letter published in the Writer’s Year Book that it wasn’t the editors’ fault that pulps were languishing, it was the publishers’ problems with “manufacturing, distribution and promotion.” Byrne goes on, “The pulps are always dying, as they died for Old King Brady and Nick Carter, as they died in 1930 for the publishers of that day, yet only the form dies. The business of supplying low-cost entertainment to mass markets always manages somehow to confound the obit writers.”

Street’s decision surprised even its own writers. Walter B. Gibson, the lead writer for The Shadow series, was banging out new stories when the bombshell was dropped.

“I was working with Daisy (Bacon, who was editing The Shadow at the time), just simply working story by story. So I turned in one, she liked it, turned in another, turned in another, and turned in another, so I went about other work for awhile, and then called Daisy — or she called me one day and says, ‘Don’t start the next one; they’re not going to ahead with it.’ Just like that,” Gibson recalled in an interview in “The Duende History of ‘The Shadow Magazine.’ ”

Fictioneer Richard Deming told Ron Goulart in The Dime Detectives that “I did not see the complete end of the pulps coming as quickly as it did, and neither did most of the editors in the field. Although all of us could see them dying.”

While the pulpwood magazines died, the “pulp”-style story would live on.

In a letter to The New York Times, Kenneth W. Scott of New York wrote, “The decision of Street & Smith to discontinue the publication of pulp thrillers and comic magazines may mark the end of another era in the history of sensational literature. However, though a waning interest in pulp adventure tales may be the trend at the moment, it seems unlikely that the demand for swiftly paced, stereotyped, inexpensive stories will ever die out permanently.”

Indeed, paperback books, comic books, and television took up the mantle from the pulps. Even a few digests remained after all was said and done, including Street’s own Astounding Science Fiction, which continues publication today as Analog Science Fiction and Fact by Dell Magazines.

And as the cottage industry of pulp magazine writing dried up, many fictioneers shifted to those emerging markets. Among those were Richard Sale, Edmond Hamilton, Julius Schwartz, Frank Gruber, Steve Fisher, Gardner Fox, and many others.

The final nail in the pulps’ coffin may have come from the decision by American News Co. to stop distributing the remaining pulps to newsstands. But Street & Smith’s move in 1949 clearly signaled the end of the pulp magazines.

About the author

William Lampkin is editor of ThePulp.Net. He is editor and designer of The Pulpster. And, he writes the Yellowed Perils blog.