Blue Book existed from 1905 to 1975, though not always as a pulp fiction magazine. It was also one of three companion magazines. I am only aware of two works that look at the overall magazine. One is an article by Mike Ashley, “Blue Book: The Slick in Pulp Clothing,” which is available on Galactic Central, and the section of Murania Press‘ The Blood ‘n’ Thunder Guide to Pulps.

Blue Book existed from 1905 to 1975, though not always as a pulp fiction magazine. It was also one of three companion magazines. I am only aware of two works that look at the overall magazine. One is an article by Mike Ashley, “Blue Book: The Slick in Pulp Clothing,” which is available on Galactic Central, and the section of Murania Press‘ The Blood ‘n’ Thunder Guide to Pulps.

Blue Book was launched by Story Press Corp., which had previously launched Red Book Illustrated in 1903, but it was called The Monthly Story Magazine for its first couple of years. Both magazines were fiction, but Red Book was an illustrated slick-paper fiction magazine aimed at women, while The Monthly Story Magazine was an un-illustrated pulp magazine, though on a higher grade of pulp paper. It has been noted that the two where more like Harper’s and Scribner’s than Argosy or The Popular Magazine in terms of the quality of the fiction.

Blue Book, which took that name in 1906, also had an insert called “Stageland” that focused on the theater, much like today you’d get stuff on TV shows, movies, and actors. This insert would later move to The Green Book Magazine, from the same publisher. Green Book started in 1909, and was also aimed at women.

Like Red Book, Green Book‘s early covers had women’s faces, surrounded by the color of the magazine. Green Book became a more pulp fiction magazine toward the end of its run, but in looking over it, I didn’t notice any authors I knew. Anthony M. Rud‘s Jigger Masters series first appeared in it in 1918. Green Book ended in 1921.

In 1929, McCall Magazines bought Consolidated Magazines, which by then owned both Red Book and Blue Book. I’m assuming the company Story Book just changed its name. By that time, The Red Book Magazine had become Redbook Magazine, and was less a fiction magazine as a women’s magazine. Interestingly, Blue Book didn’t become Bluebook until 1952.

But back to Blue Book. The early years of the magazine are considered up until 1914. There were some notable piece by folks like George Allan England, a science-fiction author who got his start there. Several of his works have been reprinted of late. While the magazine has been noted for its science fiction and fantasy works in the 1930s and ’40s, that wasn’t a big part of what they carried. The magazine would become known for its adventure fiction.

It can be thought of as the father of Adventure magazine, and Ashley pointed out a former editor was responsible for starting Adventure. Reprints from English writers like William Hope Hodgson and later Agatha Christie were done as well.

The magazine soon stated that they would not run any serials, something that other pulp magazines did to keep their readers coming back. All stories would be complete, but they would do series. This rule on no serials would later be dropped.

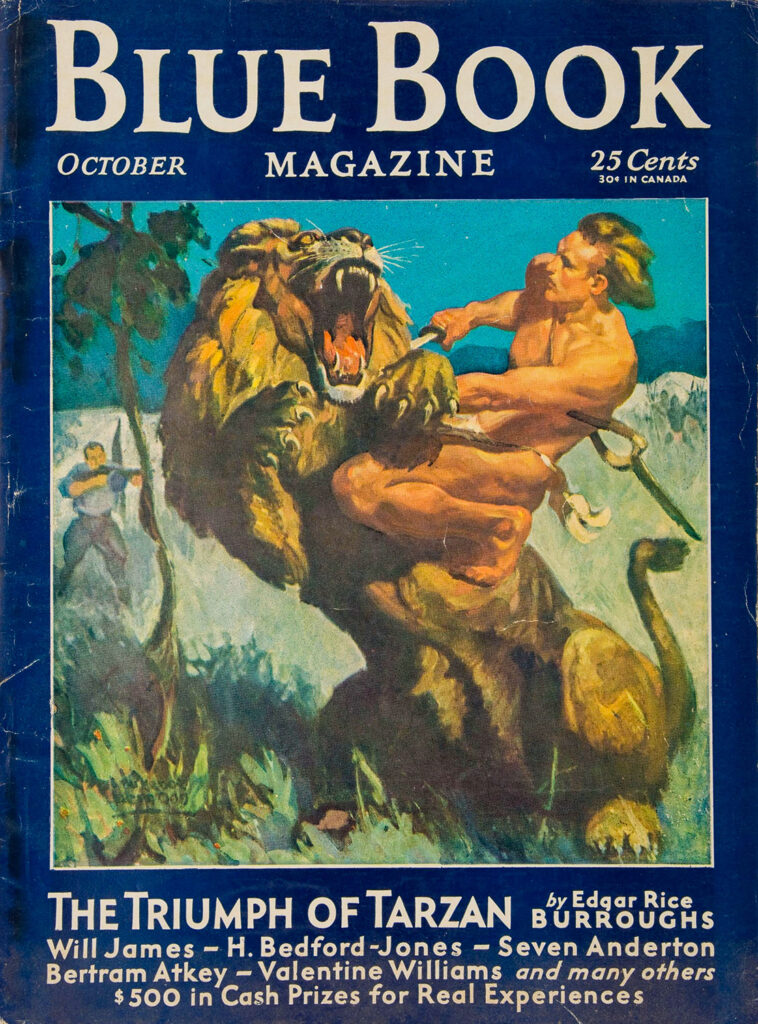

The heyday of Blue Book would be from 1914 to 1927 and then its golden age from 1928 to 1940, again per Ashley. Here we would see greats like Edgar Rice Burroughs and H. Rider Haggard in the magazine, among others.

Burroughs had some of his Tarzan, Pellucidar, and other novels published here for several years. The prolific H. Bedford-Jones wrote a LOT for Blue Book. I believe it was his biggest market, and he sometimes had four works in an issue!

But what I was surprised to learn is that Bedford-Jones was not the magazine’s most prolific author. That honor goes to Clarence Herbert New (1862-1933), whose main work was his “Free Lances in Diplomacy” series. This series started in the March 1910 issue and lasted until August 1933 — for about 275 stories! He wrote other series and stories as well.

A new author in the ’30s was British writer William J. Makin, who kind of took New’s place. He wrote heavily for the next 10 years; the main one being a long series about a British agent in Arabia known as Red Wolf. Another was William Chester‘s Kioga series, which was a decent replacement for the Burroughs works when they could no longer afford him. Chester’s Kioga would be made into serials and later reprinted. The series was set in an unknown Arctic land, and told the story of Kioga, a white boy who was raised by the Indians who lived in this lost land.

Now, as to Bedford-Jones, Blue Book published 360 of his stories, including seven series and six novels. There were probably more, as Bedford-Jones had to use some of his pseudonyms; two main ones used here being Gordon Keyne and Michael Gallister.

His series included “Arms and the Man,” which started in February 1935 and ran for 28 stories, and explored man’s discovery of weapons over the centuries. Next is “Ships and Men” (began January 1937 for 34 stories), ostensibly written with Capt. L.B. Williams for technical advice, though this is just one of his pseudonyms. Here we learn of mankind’s naval exploration and development of boats. June 1937 kicked off “Warriors in Exhile” for 17 stories about men of the foreign legion.

In July 1938, under the alias Michael Gallister, he began his stories about fireboats with “Harbor Hazard” (four stories) and his series about man’s conquest of the air with “The Bag of Smoke” (July 1939 for five stories). A different series launched in November 1938 with the “Trumpets From Oblivion” series (13 stories) under his real name. This was a rare science-fiction series from him that had a machine that allowed the viewing of the past to show the origins of various myths and legends. There are another handful of longish series from him as well.

In the 1940s, Blue Book had become a more mature magazine, and was aimed more at men around 1945, similar to what happened to Argosy. I’m not sure if it can be counted as a “men’s adventure magazine” just yet, as it doesn’t appear to have that over-the-top aspect or the risque factor. It would get named Bluebook in 1952, with the byline “Adventure in Fact and Fiction,” and magazine would end in 1956. Then it was sold to a men’s adventure magazine publisher and brought back as Bluebook for Men in 1960 as a more explicit MAM, especially from 1967 to its demise in 1975.

But certainly from it’s golden periods, there was a lot of great fiction written, some of it having been reprinted. Certain authors like Burroughs, Haggard, Hodgson, Christie, etc. have been keep in print for decades. Lesser-known but still excellent authors are being brought back into print, such as George Allan England and H. Bedford-Jones.

For Bedford-Jones works, we have “The Wilderness Trail” (his first in the magazine), “Ship and Men,” “Warriors in Exhile,” “The World Was Their Stage,” “The Rajah From Hell,” “One More Hero: The Cases of the Fireboat Men,” “Treasure Seekers,” “The Sphinx Emerald,” and others. More are slowly coming back from Steeger Books and others.

I was shocked to find that the prolific Clarence New has had very little reprinted! Two issues of High Adventure has reprinted some of his Free Lances series, in #159 and #163, a total of 16 stories, and Wildside Press put out Unseen Hand, but I have no idea what it has.

William Chester’s Kioga series was reprinted back in the ’70s, but its no longer available. William J. Markin, who had books printed in his time, has only The Garden of TNT, which is a complete reprint of his Red Wolf series from Black Dog Books. There are probably others I’ve missed.

But overall, it was a great pulp with a lot of good works in it. Keep an eye on the several reprinters out there to see what they put out.