What came before the pulp magazines in the U.S. are referred to as “dime novels”, though there were several formats used. I have posted on several reprints of them, but not done a specific article on the dime novels.

What came before the pulp magazines in the U.S. are referred to as “dime novels”, though there were several formats used. I have posted on several reprints of them, but not done a specific article on the dime novels.

In the U.K., the equivalent to them were referred to as “penny dreadfuls” and the term “story papers” were used there for similar works aimed more at boys. In the U.S., story papers also existed prior to the dime novels earlier in 1800s, and their format was subsumed by dime novels. All of these were treated as periodicals, not as books as we know them today. Thus even if dime novels look similar to paperback books, which many did later on, they were treated as periodicals.

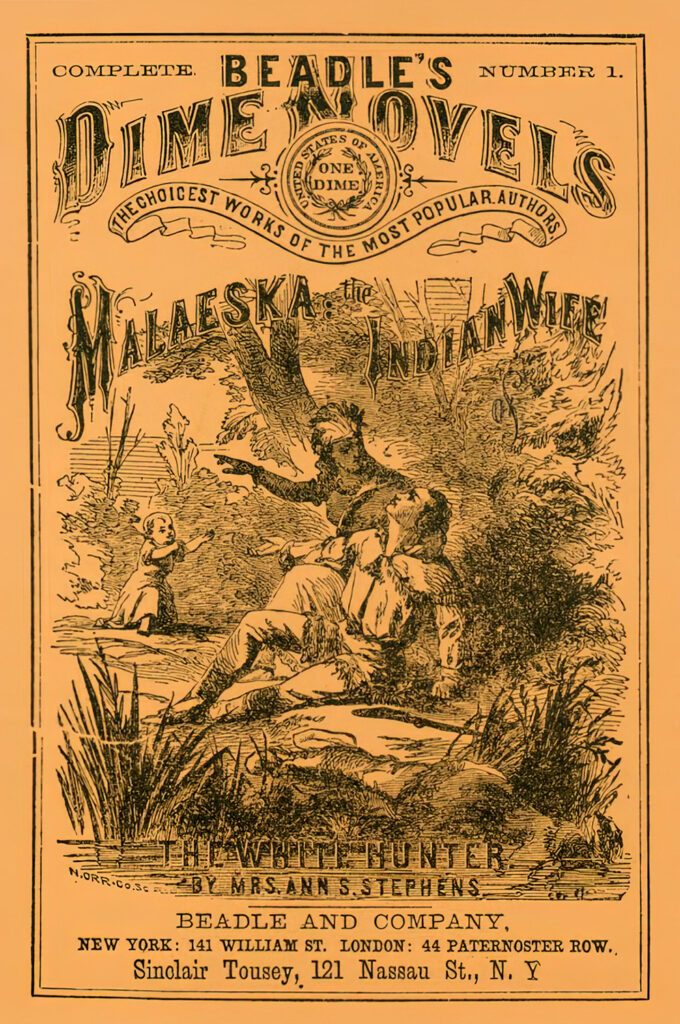

“Dime novels” is thus an umbrella term for several formats of popular fiction that existed from the 1860 until 1921. The term started when Beadle’s Dime Novels began in 1860 in a 4- by 6-inch format, publishing “Malaeska, The Indian Wife of the White Hunter.” But other formats were also used. Some used a larger 8- by 12-inch size on newsprint, running two to three columns of story, which is how “story papers” looked like. Regardless of size, early on they would serialize several novel-length works, which would later be reprinted in single issues, but regardless the series often ran several hundred weekly issues. The series could run a continuing character, or each issue could be a different character.

Later on, some stories would be reprinted in smaller formats similar to paperback books, though usually saddle-stitched with the covers often being the same type of paper as the interiors. Some reprints were a nickel, thus called “nickel weeklies”. Color printing was used for the covers later.

In fact, the number of formats is confusing. Equally so is that some series would be reprinted by a different publisher in a slightly different format. This makes sense as they were treated like periodicals, not books. So if you missed when they came out, it might be hard to get earlier issues. But if a publisher reprinted the entire run of a series, in a new format and title a few years later, they would sell again. And again.

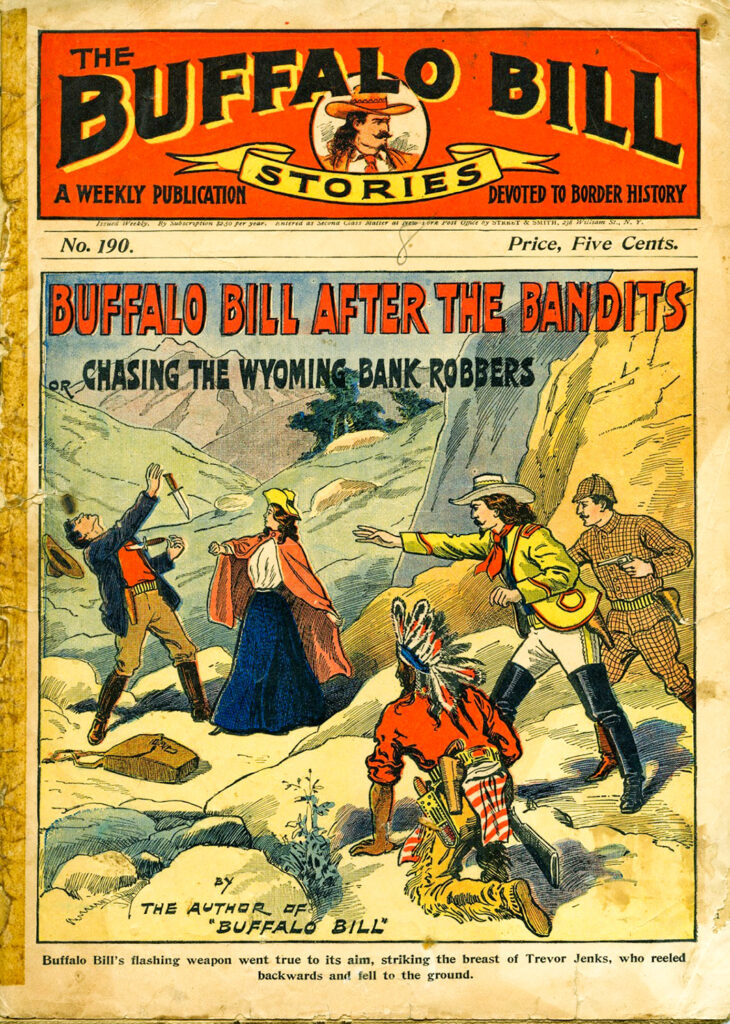

Genres were mixed. In the 1860s and ’70s, western characters were most popular. Buffalo Bill and Deadwood Dick were two ongoing characters that were very popular. In the 80s and 90s, crime and detective stories became popular. Here you had characters like Old Sleuth, which was the first time the term “sleuth” was used for a detective. The publisher even copyrighted the name, so others couldn’t use it. The Old Sleuth was actually a young man who disguised himself as old, and ushered in a slew of other detectives like Old Cap Collier and Old King Brady. But the most popular one was Nick Carter (whose father was Old Slim Carter), who transcended the dime novels into the pulps, radio, movies, tv, and a later men’s paperback series (tho some of the later ones were Nick in name only).

Genres were mixed. In the 1860s and ’70s, western characters were most popular. Buffalo Bill and Deadwood Dick were two ongoing characters that were very popular. In the 80s and 90s, crime and detective stories became popular. Here you had characters like Old Sleuth, which was the first time the term “sleuth” was used for a detective. The publisher even copyrighted the name, so others couldn’t use it. The Old Sleuth was actually a young man who disguised himself as old, and ushered in a slew of other detectives like Old Cap Collier and Old King Brady. But the most popular one was Nick Carter (whose father was Old Slim Carter), who transcended the dime novels into the pulps, radio, movies, tv, and a later men’s paperback series (tho some of the later ones were Nick in name only).

Science fiction also existed in the dime novels, starting with the classic Steam Man of the Prairie, which launched a series of “edisonade” characters like Frank Reade, Frank Reade Jr., et al that inspired the later Tom Swift. These I have specifically posted on.

Several companies were involved in publishing dime novels, but most didn’t succeed the change-over to pulps. Beadle and Co. is a major one I always hear of, but there are several others including George Munro, Robert DeWitt, J.S. Ogilvie, Arthur Westbrook, and Frank Tousey.

Street & Smith was another, but S&S succeeded in moving into the pulps, starting in 1910. This included changing over their Nick Carter Stories weekly to the weekly Detective Story Magazine in 1915, which they did with several other of their dime novel series (New Buffalo Bill Weekly became Western Story Magazine in 1919, and New Tip Top Weekly became Tip Top Semi-Monthly in 1915, etc.). Why other publishers didn’t do this, I have no idea.

Thus pulps and dime novels existed side-by-side from around 1900-15, with pulps eventually winning out. There were several reasons for it. One, postal rates were no longer favorable for the dime novels. Another was simple economics of cost. For the same price of a dime novel, that would give you one novel, you could get a pulp magazine that would give you a novel plus several other stories and features. Which would you choose?

There are several sources of information on dime novels, though they are hard to find. Dime Novel Roundup is a fanzine devoted to the dime novels that is still published quarterly. The Popular Press did some works on dime novels if you look and I’ve posted on several of them.

Joseph L. Rainone‘s Almond Press has put out several works on dime novels, including a price guide. And I am finding more and more dime-novel works being reprinted by various people, thanks to the power of print on demand. For instance Darren Németh has been doing his “Page Turner Series” and others with Kickstarter and later through his Giant Squid Audio Lab Co. I’ve posted on several and plan more. And a few people, like Joseph A. Lovece, are writing new works inspired by the dime novels (“new dime novels”?). I’ve discovered more POD dime novel reprint series on Amazon as well, reprinting series like Joe Phenix and Frank Reade, Jr., among others.