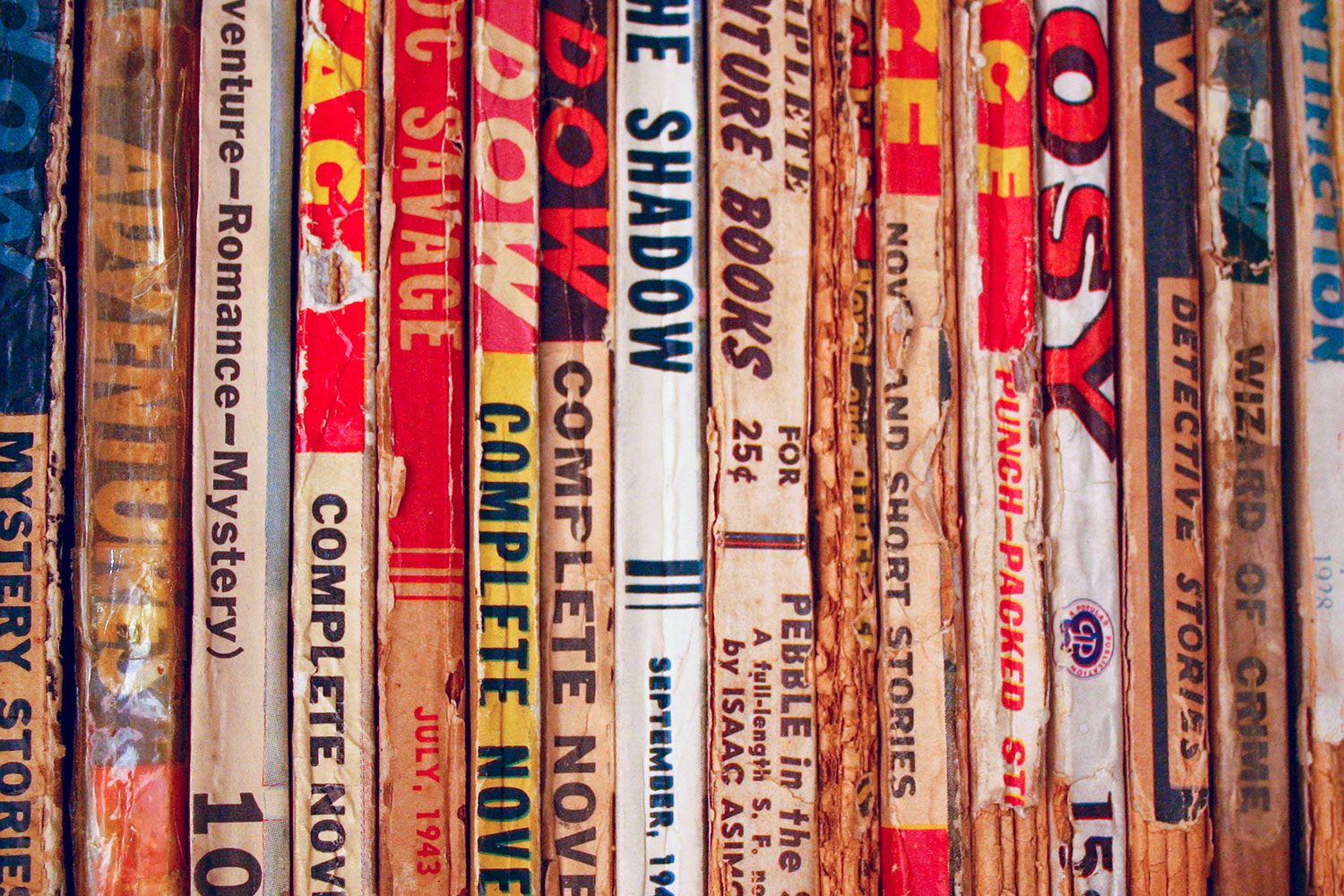

“Pulp” is a medium. It is a pulpwood magazine.

“Pulp” is a medium. It is a pulpwood magazine.

It is not a style of writing. Not a genre of fiction. Not one end of a spectrum of literature.

Pulp is not science fiction. Fantasy. Horror. Western. Romance. These are fiction styles that appeared, along with countless others, in the pulp magazines.

Pulp isn’t paperback books. Pulp isn’t hardback books. Pulp isn’t comic books. Pulp isn’t artwork.

Pulp was a method of distribution of popular fiction on pulpwood paper from the late 1890s through the late 1950s. Pulp is no more.

It’s not a set of rules. It’s simply a definition of “pulp.”

Don’t like the definition? Does it sound too restrictive? Take it from an actual pulp fictioneer when asked, “Tell us a little bit, in a few brief words, about the pulps and what we mean by that term”:

The term is a somewhat of a misnomer. It was a thing that was used among writers to differentiate as to the kind of markets to which they sold their stories.

That’s a quote from Walter B. Gibson, who was churning out a million words a year during the heyday of the pulp magazine. He’s a pretty reliable source.

See Gibson say it for himself. It’s the first comment out of his mouth.

He didn’t call the stories he or other fictioneers wrote “pulp.” He called the medium “pulp.”

No matter how much you wish to call a story a “pulp” story, it is wrong to do so unless you are referring to a story printed in the pulp magazines.

There are already perfectly clear, widely recognized names for styles of stories — and those names also apply to the stories that appeared in the pulps: science fiction, fantasy, horror, western, romance, sports, war, aviation, and the list goes on.

Descriptions such as pulp-like, pulp-inspired, pulp-derived and, to a much lesser degree (because it’s kind of a stupid word), “pulpy” work when you’re talking about fiction written after the pulp magazines died.

Though pulp fiction is dead, pulp fandom lives on and will live as long as there is interest in reading stories published in the pulps — whether in the crumbling magazines themselves, in reprint books and replicas, or on digital devices.

That said, the phrase “new pulp” is a whole different can of worms. Current writers, publishers and readers are using it to describe new material written as a homage to the pulp-magazine era.

I can live with that being called “new pulp.” They are creating a new style of genre fiction.

But, please, “pulp” refers only to those many, varied stories from the old pulp magazines.

So Jazz is just horns and always has to be be-bop.

No. Jazz is a style of music. Bebop is a style of jazz.

The analogy would be: A band is not jazz. A band is not bebop. But a band has played jazz and bebop, as well as other forms of music.

A composer writes jazz/bebop for a band; he doesn’t write band.

I can’t believe you’re arguing semantics like this. Pulp lives and breathes — the name may have come from the type of paper it was printed on but the spirit of pulp (the escapist fiction that’s written to cheaply entertain) is doing quite well. This is like saying that no one can call U2’s next album a record since it won’t be printed on vinyl.

Thanks for that link to Walter Gibson interview, Bill. Great stuff.

Hi, Duane,

I’d only seen short clips of him before; I thought the half-hour interview was great, too.

Glad the PulpRack is returning, albeit in a different form. I was sorry to see it go.

Cheers!

You’d better start writing to various dictionary publishers, because they all sport definitions in line with NewPulpFiction.com’s definition.