Well, turn back the clock back 22 years — and then ahead several million — and you have “Genus Homo,” a pretty solid SF novel by L. Sprague de Camp and P. Schuyler Miller.

Well, turn back the clock back 22 years — and then ahead several million — and you have “Genus Homo,” a pretty solid SF novel by L. Sprague de Camp and P. Schuyler Miller.

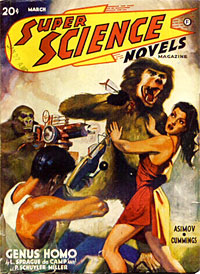

It was originally published in the March 1941 number of Super Science Novels (the temporarily renamed Super Science Stories), a typically lackluster SF pulp edited by Frederik Pohl that, while it did occasionally run a good story, is most notable for publishing the early works of a number of now well-known writers.

Pierre Boulle‘s 1963 novel, “Planet of the Apes,” is primarily about a human mission to a planet orbiting Betelgeuse that turns out to be inhabited by intelligent apes (with a twist at the very end); whereas the 1968 and 2001 movies take place on Earth, but in the future.

“Genus Homo” opens with a busload of people suddenly trapped in a familiar SF trope: something, possibly an earthquake, causes a tunnel cave-in burying the bus and releasing an recently discovered gas that puts the bus passengers and those around it into suspended animation for millions of years.

But unlike “Planet of the Apes,” the two dozen human survivors appear to be the only humans in the distant future of “Homo Genus.” Earth has been reshaped by geological and evolutionary forces into a world only slightly familiar to that left by the new arrivals in 1939.

Once the group has pulled themselves from their pit of slumber, the real fun of the novel begins.

The survivors are a hodgepodge group: four scientists on their way to a science convention in Columbus, Ohio, a night-club hoofer and the girls in his act, the bus driver, a lawyer and his businessman friend, a school principal and several of her teachers, a family of three (who were driving in a nearby Chevrolet when the accident happened), and other assorted individuals. They are led by Stanford chemist Henley Bridger, or just Bridger, as they explore their new world.

Just as in de Camp’s previous “Lest Darkness Fall” (originally a short story in Unknown, December 1939, later expanded into a novel) and “The Wheels of If” (Unknown, October 1940), de Camp and Miller are able to create a whole new history — and world, in this case.

We get to explore, along with the 25 survivors, this new world teeming with evolved creatures that are familiar but different from those of our world.

Emil Scherer, a mammalogist, identifies one of the first creatures they see: “Let’s call it a gopheroid. ‘Gopher’ for ‘gopher’ and ‘oid’ for ‘something like’; in other words, something like a gopher.”

Unfortunately, every newly discovered creature from then on gets tagged as an “-oid”: batoid, catfishoid, minkoid, woodchuckoid, you get the picture. It may have been a novel naming scheme in 1941, but it reads awkwardly and almost comically today.

About halfway through the novel, the survivors come upon intelligent gorillas who capture the never-before-seen humans for zoological study. Unlike “Planets of the Apes,” where humans mirror today’s apes as wild animals, there apparently are no other humans in the world of “Genus Homo.” The gorillas are curious about the humans because they have found relics from when humans ruled on Earth.

Gorilla scholar T’kluggl eagerly asks the humans: “Being persons of learning, you can appreciate the great importance of your arrival here to us. As soon as possible, all of you must write down everything that you can remember of your former lives and of the world in which you lived. That includes not only the history and technics of your species, but your own histories, even to the most trivial matters.”

De Camp and Miller create a rich culture and history of the apes, which the gorilla scholar T’kluggl explains to the curious humans. For instance, the gorillas’ government is scientifically organized. “We have a class of scientists whose principal duty is to study the machinery of our government and devise ways of improving it,” T’kluggl says.

He explains that the gorilla government is headed by “28 individuals at Mm Uth. They are elected from a group of 144, who are selected every six years by competitive examination. Our scientists have found that, in these latitudes and with the volume of work required of such a group, 28 is the best number.”

T’kluggl also details the other species of apes.

The chipanzees (or G’thong-smith): “They are a very clever lot, but nervous and quite irresponsible. Their history is full of strange stories of civil war, conspiracy, and murder. But they built some magnificent cities, with huge stone buildings. They look down on us because they say that we cannot make pictures and music, and cannot recite long pieces of writing as beautiful as theirs.”

The orangutans (or Toof K’thll): “Early in their history they learned to build great ships. They have a tradition that they originally lived on islands which slowly sank, so that they became seafaring to save themselves. Now they have small settlements in widely separated parts of the world, and travel the oceans in their ships.”

And the warlike baboons (Pfenmll): “They have a fantastic system of government. When one of them, by use of force and fraud, has attained the supreme power, he rules until he dies, when his eldest male offspring becomes his successor automatically. That is, if he is not murdered before he can succeed. This strange way of selecting their rulers is one reason why we question that the Pfenmll will ever become really civilized. We gorillas have done many unwise things in the course of our history, but we have never left the choice of our officers to the caprices of heredity!”

Unfortunately, the culture and history of the apes is covered in just two chapters. It is pre-empted by an invasion of baboons. It would have been interesting to have our human protagonists spend more time exploring the simian civilizations.

Instead the final chapters are devoted to battling the baboons.

Sadly, de Camp and Miller fail to put the human scientists’ knowledge to good use in the book. Other than identifying new animals, the only real benefit the humans provide the gorillas is the creation of a mounted brigade of gorillas riding piglike creatures — and that’s thanks to Macdonald, the Pittsburgh cop.

I wish the scientists had come to the gorillas’ aid in the way archaeologist Martin Padway put his knowledge and skills to work in the 6th century in “Lest Darkness Fall.”

Otherwise, “Genus Homo” is quick, entertaining reading.

Some behaviors are so automatic, like the example of not touching a hot stove, that one almost thinks they are instinctual–as if we were born with the knowledge not to touch a hot stove–and whenever I see a reproduction of a pulp magazine on a blog, I almost instinctually do not expect much. Usually the blog writer has not even read the magazine or if he has, he does not make the effort to say anything intelligent about it. Contrary to my expectations when I saw the cover of Super Science Novels Magazine on your blog, you provided an informative and insight piece on it.

The way you describe how the story revolved around scientists, human or otherwise, made it sound as if the story would have catered to an adolescent, nerdy worldview–exactly how a contemporary person might have viewed the personality of the average reader of this magazine in 1941. I shall not cast any further stones at the readers of Super Science Novels lest I hit myself in the process. About your observation that adding the suffix “iod” to each animal name sounds comical today, I think it probably sounded comical in 1941 too.

Although I still shall not be putting my hand on hot stoves, I know to expect an entry worth reading when I see a cover reproduced from a pulp magazine on your blog.