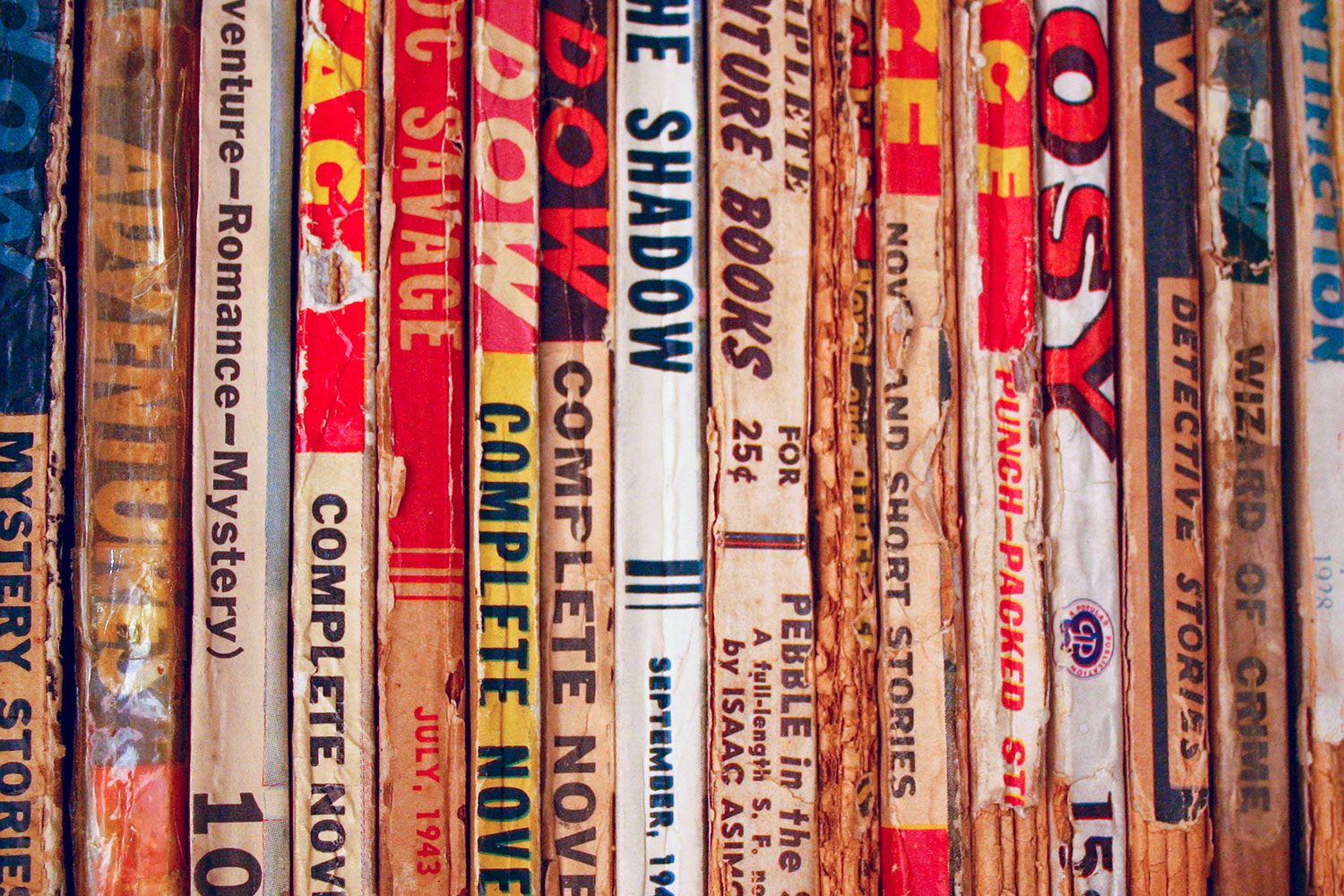

I just finished reading Red Harvest. It’s the first novel by legendary pulp fictioneer Dashiell Hammett, though it was first published as a four-part series of stories that appeared in Black Mask from November 1927 through February 1928.

I’ve been a fan of Hammett’s character, the Continental Op, ever since my buddy Charles Corder gave me a copy of the Vintage Books paperback The Continental Op back in the mid-’70s.

Earlier in the summer, I bought The Big Book of the Continental Op, edited by Richard Layman and Julie M. Rivett. The print version of the book collects all 28 stories and both novels featuring the unnamed investigator from the Continental Detective Agency.

John Wooley and John Gunnison discussed Hammett at this summer’s PulpFest. (You can listen to their talk on the Pulp Event Podcast, by the way.) Since that presentation was fresh on my mind, it seemed like a time to pick up the Op.

I had read many of the stand-alone short stories over the years, but not the novelized versions of the serials. Hammett followed up Red Harvest with The Dain Curse, which was originally serialized in Black Mask a year later, from November 1928 through February 1929.

The Op — his name is never revealed to the reader, and it really doesn’t matter — is a short, heavyset fellow in his mid-40s (that was considered “middle-aged” in that era). He’s not the hard-boiled detective you see depicted in the movies or TV, and often in the other pulps. As I was reading Red Harvest, the actor Paul Giamatti popped into my mind’s eye. He would be ideal as the Op if someone wanted to make a movie. (Hint, hint.)

In Red Harvest, the Continental Detective Agency has been retained by a newspaper publisher in the small Montana mining town. Shortly after the Op arrives in Personville — derogatorily deemed “Poisonville” for its corruption — and before he can meet with the publisher to learn why the agency had been hired, the publisher is murdered.

Upon a bit of investigation, the Op realizes the balance that held numerous criminal elements at bay in Personville is faltering, and the various sides are beginning to vie for the upper hand.

Now, if you’ve seen Akira Kuosawa‘s Yojimbo (or Sergio Leone‘s A Fistful of Dollars, or Last Man Standing, starring Bruce Willis), you know the outline of the plot of Red Harvest. The Op, going against all the rules of the agency, takes on the task of cleaning up Poisonville by playing the sides murderously against one another.

Red Harvest is a fun read. But in typical pulp fashion, it relies heavily on tags and action over characterization. There’s little description in the Op’s first-person account of the events, but Hammett does manage to get a few thoughtful nuggets into the Op’s inner dialogue. Such as:

He said things couldn’t go on the way they were going. We were all sensible men, reasonable men, grown men who had seen enough of the world to know that a man couldn’t have everything his own way, no matter who he was. Compromises were things everybody had to make sometimes. To get what he wanted, a man had to give other people what they wanted.

Wooley, in the PulpFest presentation, mentions that Hammett was more detective than writer. And that’s evident as you read the book. He’s more focused on the detective action than the literary flow. But that also reflects the hard-boiled style that Hammett and other pulp detective writers were creating. It’s straight-to-the-point fiction with no time for adjectives or actions that don’t directly move the plot forward.

At the same time, that doesn’t mean Hammett is a bad writer. Rather, he is writing in different form to a different audience than, say, contemporary Ernest Hemingway, who also wrote in a lean, terse style.

I strongly recommend picking up a story about the Continental Op if you’re looking for a good pulp story. Heck, just a good story. Or, if you’d like to dive in deeper, give Red Harvest a shot.

Now, I think it’s time to shift gears and pick up a Clifford Simak book. Then maybe move on to The Glass Key.

CORRECTION: I mistakenly referred to John Wooley as John Locke in the original version of this post. It has been corrected. Mea culpa.