One hundred twenty-five years ago, “Argosy” introduced the pulp magazine to a populace eager for inexpensive, popular fiction.

The history of pulp the magazine in America is a brief one.

The process of chemically treating wood pulp was developed in the 1880s. Pulp paper was made from wood that was shredded to fibers and reduced to a pulp mass by chemicals. Then the substance was pressed and dried on a mesh mold.

The outstanding quality of pulp paper, from a publishing point of view, was that it was cheap.

Before the 1880s, most magazines targeted the educated middle and upper classes. These “slick” magazines — named for the high-quality, glossy paper — were often family-oriented magazines, containing factual articles, fiction, and poetry.

Pulp paper is coarse and highly absorbant. The acidic nature of the chemicals used in the process creates the yellowing or browning effects. Or, as fictioneer James Gunn aptly described in Alternative Worlds: The Illustrated History of Science Fiction: “It contained within itself the acid of its own destruction.” Pulp paper also becomes brittle with age, and flakes drop off.

Fanzine flashback

This article originally appeared in The Pulpster (No. 6; August 1996) for Pulpcon

This article originally appeared in The Pulpster (No. 6; August 1996) for Pulpcon

The paper itself is thick, and so the pulp magazines tended to be bulky, usually a half-inch or more thick. As part of the cost savings, the edges of the magazine pages were usually left untrimmed. The coated-stock magazine covers used inks made from coal tar dyes, creating bright, garish covers.

The covers could extend beyond the actual body of the magazine, leading to bending and tearing. Sizes of pulp magazines varied between the standard 10- by 7-inches, to the digest (5-1/2- by 8-1/4-inches) and bedsheet (9-3/4- by 12-inches) sizes; and 128 was a common page count for the pulps.

Since the 1860s, the dime-novel industry had flourished, by and large publishing adventure fiction on newsprint. Wild west and detective fiction were the main staples of the dime novels.

A new magazine argosy

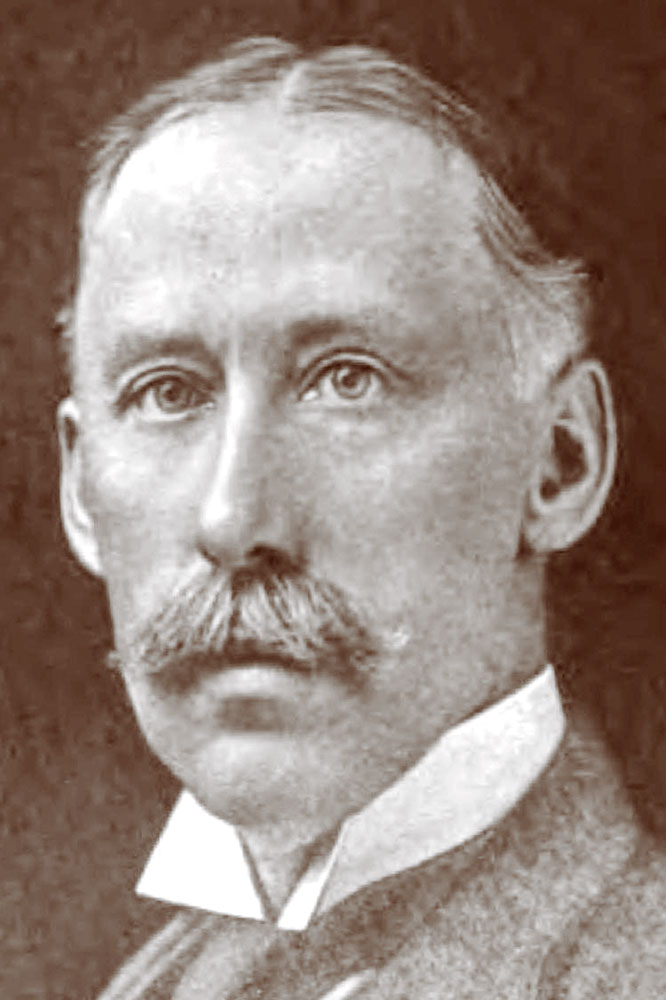

The Golden Argosy was first published December 1882 by Frank Munsey. Like other magazines of that era, it dealt with a broad range of subject matter. In 1896, however, The Golden Argosy became Argosy — as Munsey experimented with 192-page magazine of only fiction for 10 cents. The pulp magazine, as we know it, was born.

Magazine circulation doubled with the change in format to fiction. Argosy‘s circulation was about 80,000 when it debuted, but had reached a half a million by 1905.

Munsey made $237,000 from Argosy sales in 1904, and $300,000 in 1907. Matthew White Jr. edited Argosy until 1928, having begun as editor of The Golden Argosy in 1889.

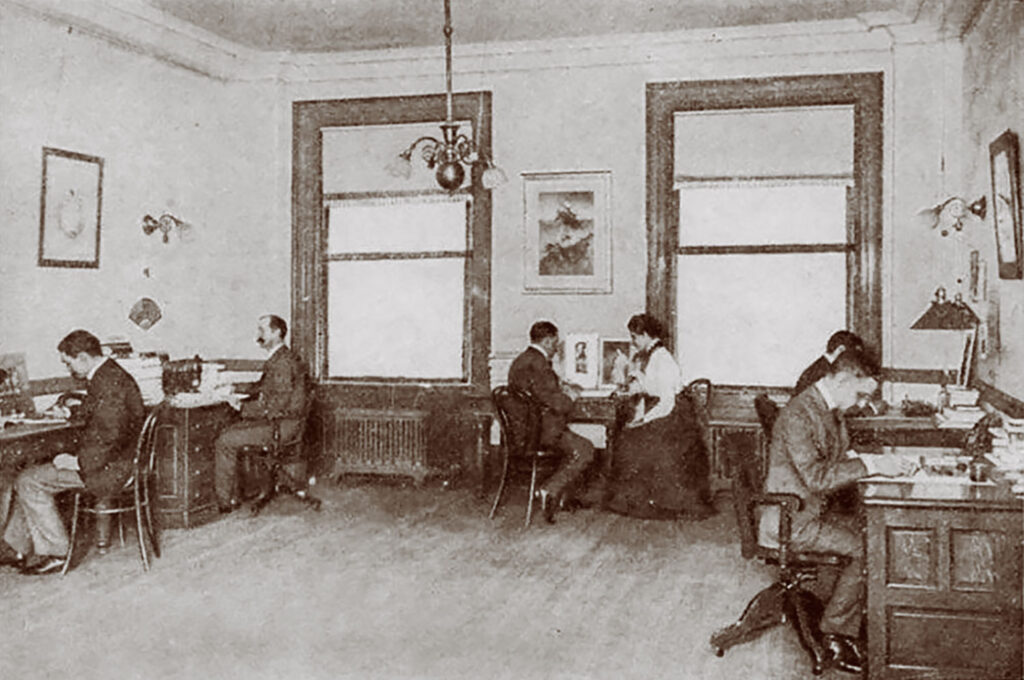

Street & Smith Publications had been in the dime-novel business, and had published weekly fiction since the 1850s. They brought out The Popular Magazine in 1903 for a young male readership, and dime-novel editor Henry Harrison Lewis was made its editor. In 1904, under a new editor, Charles Agnew McLean, The Popular Magazine went to an all-fiction format aiming for a broader audience, and increased its page count from 96 to 194.

In the early part of the century, competition started up among the pulp magazine publishers, each one eager to capture a share of the growing and profitable market.

Munsey introduced a new pulp magazine in 1905. This was All-Story, with Robert H. Davis as its editor (a position he retained until 1926). In the first year of publication, All-Story boasted a circulation of 250,000.

The Story-Press Corp. put out The Monthly Story Magazine in 1905, and it is better known to many readers by its subsequent name, The Blue Book Magazine.

In 1906, Street & Smith launched People’s Magazine as a companion to The Popular Magazine. That same year, Munsey countered with The Scrap Book, under the editorship of Robert Davis. Diverging from an all-fiction format, Munsey experimented by dividing the magazine into two sections — a slick, front section with articles, and a lesser-quality, book-paper section for fiction — but returned to the old all-fiction format in 1908. It moved to pulp paper in 1911.

References on Pulp History

Among the reference works consulted in preparation for this article:

- The Pulps, edited by Tony Goodstone, Chelsea House Publishers, New York, 1970

- An Informal History of the Pulp Magazines, by Ron Goulart, Ace Books, New York, 1973

- The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, edited by Peter Nicholls, Granada Publishing, London, 1979

- Alternative Worlds, by James Gunn, Prentice-Hall Inc., New Jersey, 1975

- The Visual Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, edited by Brian Ash, Pan Books, London, 1977

- A Pictorial History of Science Fiction, by David Kyle, Hamlyn Publishing, London, 1976

In 1906, Munsey brought out the first specialized genre pulp, Railroad Man’s Magazine, and in 1907, he brought out Ocean, with 192 pages of sea stories. Ocean, however, lasted for only one year, when it became The Live Wire in 1908. The Live Wire was a complimentary volume to The Scrap Book. But later that year, it merged with The Scrap Book. At the same time, Munsey titled the fiction section of the pulp The Cavalier, and then converted The Cavalier into a separate publication altogether. The Scrap Book would last until 1911, when it once again merged with The Cavalier as a weekly publication.

Genre fiction

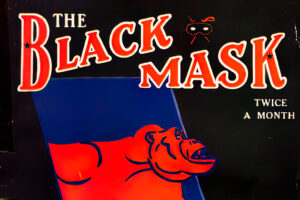

Genre fiction had been around for some time. Frank Reade’s Boys of New York, which specialized in invention tales, had been in circulation since the 1890s. Many pulp genre titles appeared after 1915, with Detective Story Monthly (1915), Western Story (1919), Love Story (1921), and Weird Tales (1923). By the end of World War I, there were an estimated two dozen pulp titles in circulation, but by the mid-’20s, there were over 200 different titles competing for sales.

Hugo Gernsback’s claim to pulp fame came from his science-oriented magazines, which evolved into the first American science-fiction pulp. First, there was Modern Electronics and Electrical Experimenter in 1913, then Science and Invention in 1923, and on April 5,1926, arrived Amazing Stories, with its scientific-romance fiction stories.

In 1920, Munsey’s publishing star was waning, and he was forced to consolidate his two best-selling publications as Argosy-All-Story Weekly in a smaller size. Munsey himself would die five years later. But he had seen the pulp magazine through to popular acceptance, and the next two decades would witness the pulps flourish in various genre titles, until other media, such as paperbacks and television would help bring an end to their popularity in the 1950s.

About the author

Tony Davis is a long-time fan of the pulps, the 1999 Lamont Award winner, and editor emeritus of The Pulpster.