While authors for a long time have hidden themselves behind pseudonyms, the use of them is a big part of the pulp magazines.

The reasons that some used pseudonyms are many. And instead of just one, some authors often had half a dozen or more pseudonyms. This has actually made it difficult for researchers to figure out who wrote what.

Many authors didn’t bother to keep their own records, and records for many publishers weren’t saved. This leaves researches to try to figure things out via writing styles and the like. And sometimes mistakes are made.

So let’s take a look at why pseudonyms were used, and who used them.

House Name

One unusal type of pseudonym is the “house name,” which is not owned by the author but by the publisher. And in many cases could be used to cover multiple authors. These harkened back to the many dime novel serial characters who were either credited to the character themselves or to “NoName” or the like. As the dime novel characters were often owned by the publisher, this made sense. This practice was also used by various juvenile book syndicates who, again, owned the characters and not the authors.

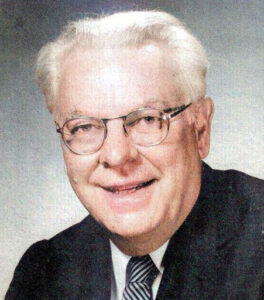

In the pulps, I’m not sure when they started to be used, but the first I knew of its use is with “Maxwell Grant” as the author of The Shadow, rather than credit Walter B. Gibson. Interestingly, Gibson created that name, using the names of two magic dealers. When you keep in mind that The Shadow, like the previous dime novel characters, was owned by the publisher, this is why. This was different from the many previous serialized characters that were owned by the authors, as well as you now had a magazine focused on and named for the character.

Hence the main reason for the use of house names was that should there need to be a new author to write the character, this can be hidden under the house name, and so most, but certainly not all, of the character pulps to follow did this. Making it more tricky is when these house names would be used for other characters, or would be used by the publisher for more wider use.

For instance, when Walter Gibson wrote the Norgil the Magician stories for Crime Busters, these were also credited to Maxwell Grant.

Street & Smith used the “Kenneth Robeson” house name for the Doc Savage novels. Lester Dent was the main Kenneth Robeson for Doc Savage, but others wrote Doc novels.

They also credited Robeson as the author of The Avenger (probably to help bring over Doc Savage fans), and as the author in the Ed Stone series in the Crime Buster pulp. But with The Avenger, Paul Ernst was really the author; however in the Ed Stone series, it was Lester Dent.

Thrilling used “Charles Stoddard” to hide Henry Kuttner for Thunder Jim Wade, but used the name for other works by other authors. Then there is the “C.K.M Scanlon” pseudonym used even more widely at Thrilling. The story I’ve heard is that it stood for “Cylvia Kleinman/Margulies Scandal,” referring to an affair by editor Leo Margulies with editor Cylvia Kleinman, whom he later married. Margulies was the head editor at Thrilling. So he was rubbing people’s noses in it?

I’m a woman

There were several female authors who wrote under pseudonyms. Sometimes the concern was that men, especially in certain genres like adventure or westerns, wouldn’t want to read a story by a woman. This sucked, but to a degree continues to this day, as witnessed by the use of “J.K. Rowling,” as it was thought a female author of a juvenile series starring a boy might be hurt by that. Examples of this in the pulps include western author B.M. Bower really being Bertha Muzzy Sinclair (Bower was her first husband’s name) and weird-fiction author Francis Stevens really being Gertrude Barrows Bennett.

See my recent article on “Women in the Pulps” for more examples of this.

Don’t let my boss know

Another reason for pseudonyms is to hide that the author is writing on the side. Sometimes they had another career and didn’t want it known they were writing fiction. There have been scientists who wrote fiction on the side such as John Taine (who was really mathematician Eric Temple Bell).

Often editors who wanted to write used them — especially if their works would appear in the magazines they edited. In a few cases, this fact was discovered, but the author still used it. George F. Worts when he first started to write, did so as “Loring Brent,” under which he created Peter the Brazen, as well as other works. But after about two years of writing, he started using his real name, but still used Loring Brent for Peter the Brazen and other works. Catherine Moore wrote as “C.L. Moore” for that reason, not to hide her gender.

A particular bizarre example of this is the case of who Allison V. Harding was, who wrote for Weird Tales in the ’40s. It was originally thought she was really attorney Jean Milligan, writing on the side. But it may be it was really her husband, Lamont Buchanan, who used it because he was an editor at Weird Tales!

I’m embarrassed (or don’t want to confuse my readers)

As a kind of variant of not letting your boss know, some authors used pseudonyms to hide that they were either writing for the pulps, or that they were writing for certain types of pulps, such as the spicy pulps.

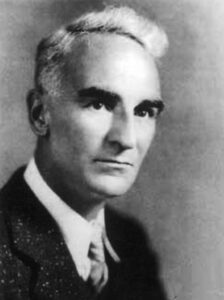

Western author Max Brand was really Frederick Faust, who wanted to avoid using his real name while writing for the pulps. But he only used this one for his western stories, using other pseudonyms for other types of works. He had about a dozen.

When Hugh B. Cave was asked to write for the spicy pulps, he used the name Justin Case for those. And there are other examples of this.

I write too much

I remember when it was revealed that Stephen King had published four works under the name “Richard Bachman” and that the reason was that he was writing “too quickly.” I think many were surprised that an author was “too quick” in writing, as most popular authors at that time usually put out at most one work a year.

Having learned more about the pulps, I find that hilarious as many pulp authors were churning out works very quickly, and I don’t think King has equaled many of them. Walter Gibson was at some point was writing about 20 Shadow novels a year, plus stories for the Shadow comic books and comic strip, and who knows how many other works. H. Bedford-Jones was also putting them out, writing over 1,000 works, sometimes working on four different typewriters at once.

But this was why many authors used several pseudonyms. If an author was going to have more than one story in the same issue, the other works had to appear under a pseudonym. One story I’ve heard for years is of a pulp magazine issue where everything was written by the same person, but I have no idea if it’s true. No one has ever said what issue or what author. But I would love to know if it is so.

Oops

I noted above that sometimes things go wrong with trying to identify the author of a pseudonymous work. And sometimes mistakes are made. An example of things going wrong in identifying an author is the case of the story “As It Was Written” that was submitted to The Thrill Book in 1919, but did not see print. It was found in the late 1970s and misidentified as the work of Clark Ashton Smith, and was published under his name in a hardback from Donald M. Grant in 1982. But it was by De Lysle Ferée Cass. I recall fanzine articles about this from the time when this was discovered after publication. Oops! I guess the name was so unusual, maybe it was thought it had to be an alias.

So hopefully this gives folks a better appreciation of the pseudonym in pulp fiction.

Great analysis. I heard that prolific magazine writer Richard Gehman once wrote an entire issue of Collier under various pseudonyms

Highly interesting, thank you!

What about Walt Coburn, in Dime Western Magazine (featured in today’s Davy Crockett’s Almanack?)

What about him?

I was making no attempt at an exhaustive listing of pseudonyms. This was a “look” at them, and explain the reasons they were used, not to list every pseudonym used in the pulps.

Edmomd Hamilton had a number of pseudonyms. He had several for pulps that would limit the number of authors. He wrote under Hugh Davison for his vampire stories. We wrote under Robert Wentworth for shudder stories. And a number of others.

Interesting article! Frederick C. Davis was one of the pulp writers who wrote under several different pseudonyms, for a couple of the reasons you mentioned, as well as some other reasons. It looks like most of the pseudonyms were used between July 1930 and April 1936, during which time he wrote over 230 stories, under his own name as well as under six different pseudonyms that I know of. Sometimes he would have two stories in a magazine under different names, and sometimes he would use different pseudonyms for different types of stories. (For instance, he would use Art Buckley for boxing stories, and his own name for detective stories.) He wrote several of the Operator 5 stories under the house name of Curtis Steele. When author Hal Dunning passed away, he was asked to write some stories under Hal Dunning’s name for a time to keep the story series going for awhile longer.

The field of juvenile series books makes extensive use of pen names. There are some personal pseudonyms of the “Mark Twain” = Samuel L. Clemens type which the library systems know how to deal with.

But there are also house names owned by a publisher or a book packager like the Stratemeyer Syndicate (e.g. “Carolyn Keene” for Nancy Drew or “Victor Appleton” for Tom Swift). These can and do represent the work of multiple writers contributing to a series.

We see some gender disguises where men write under female pen names and women write as men. The key was to find a name that would best appeal to the perceived market.

Some of these authors (and their pen names) were also used in periodicals such as story papers. Edward Stratemeyer contributed many stories to story papers such as Golden Days, Argosy, Good News, and Golden Hours. He owned Bright Days which ran for less than two years and he wrote nearly everything in it. Stories appeared under several pen names, both established and new ones.

Another use of pen names that is not covered in this article but probably does appear in the SF and pulp areas is the use of a real person’s name as a pseudonym. Most often this occurred when an author died and the publisher wanted to continue the established series.

L. Frank Baum’s name appears on The Royal Book of Oz even though it was wholly the writing of Ruth Plumly Thompson.

Irene Elliott Benson wrote two Camp Fire Girls volumes but her name was used for other similar stories by other writers.

Helen Wells started the Cherry Ames nursing series and the Vicki Barr flight stewardess series. Wells wanted to write for television so moved on (for a time). The books had been promoted as forthcoming so they appeared under the “Helen Wells” name even though Julie Campbell Tatham wrote Cruise Nurse (1948) and The Secret of Magnolia Manor (1949).

Bringing this back to pulp authors, William B. Gibson who is pictured in this article wrote some juvenile series books, including books in the Biff Brewster series (though not all of them) and the last Vicki Barr book, The Brass Idol Mystery (1964) as “Helen Wells.”

Exploring these authorship issues has been one of the more interesting aspects of writing the Series Book Encyclopedia.

James D. Keeline